Growing Waianae homeless camp at center of dispute at harbor

DENNIS ODA / DODA@STARADVERTISER.COM

Duke Heu stands at the gate to his shelter in the Pu‘uhonua O Waianae homeless encampment near Waianae Small Boat Harbor.

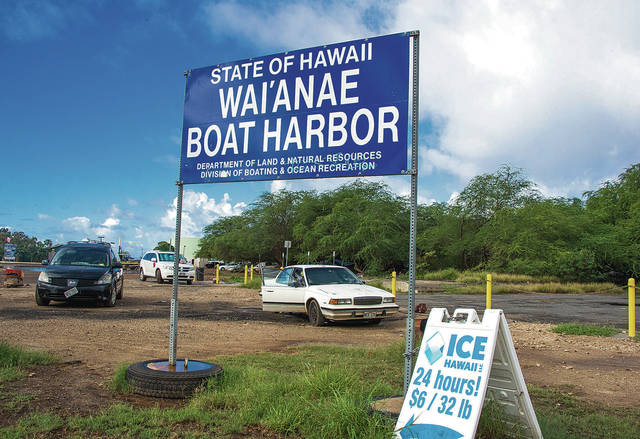

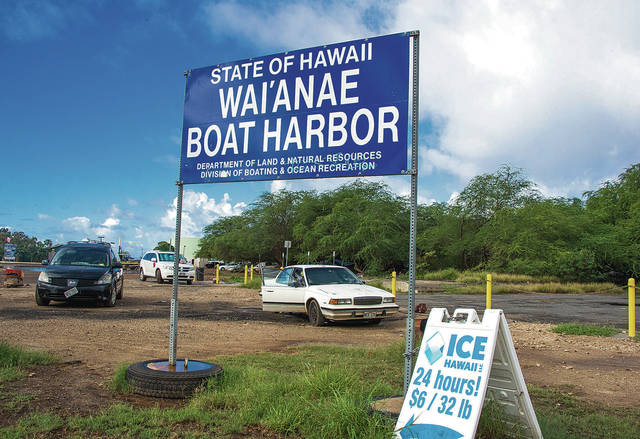

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARADVERTISER.COM

Homeless live in several cars parked near the Waianae Boat Harbor sign on Farrington Highway.

State and city lawmakers once looked at one of Oahu’s biggest homeless encampments — Pu‘uhonua O Waianae next door to the Waianae Small Boat Harbor — as a potential model for what government-sanctioned homeless “safe zones” could look like across the islands.

But city Councilwoman Kymberly Pine, who represents the area, has been getting complaints that homeless people from the encampment are dumping human waste into nearby Pokai Bay — just one issue on a mounting list of problems being linked to the homeless community led by longtime resident and homeless advocate Twinkle Borge.

“The Council has taken a stance that the type of safe zones that we want are safe zones that have sanitary conditions, roofs over people’s heads, security and an environment that does not destroy our natural resources,” Pine said. “So the Council would not really consider this a type of safe zone that would be really successful. I deeply respect Twinkle and what she is trying to do out there to the best of her ability, but many Waianae residents are now concerned about the natural environment of the area. Either they actually put houses there or bathrooms there and security there, or they find another location with all of the assistance they need. We are at risk of being forced to shut it down.”

RELATED

>> Camp residents are expected to follow rules

>> ‘Rare ecosystem’ being destroyed as homeless move in

State Department of Land and Natural Resources officials worry that occupants living in the oceanfront encampment are running up the harbor’s water bills while destroying cultural and natural resources on the 19.5 acres of DLNR land between Waianae High School and the harbor — allegations that some of Pu‘uhonua O Waianae’s homeless dispute.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

“It’s too easy to blame the homeless,” said Moki Hokoana, 45, who has lived in the encampment for eight years and has no intention of leaving. “It’s the outsiders that cause the trouble.”

For instance, the encampment gets blamed whenever people dump rubbish along Farrington Highway, including household appliances.

“It’s not us,” Hokoana said. “What are we going to do with water heaters?”

But Ed Underwood, administrator for DLNR’s Division of Boating and Ocean Recreation, can run down a long list of problems at the boat harbor tied to the occupants of Pu‘uhonua O Waianae:

“Often they just make a giant pile of trash in the harbor and we’ve had to clean up that pile,” Underwood said. “There’s vandalism in the bathrooms. They’re flushing cans down the toilets. They leave water running. It’s a never-ending battle. In my opinion, if you’re going to do safe zones, you’re going to need to provide social services, water, restroom facilities and all of that. There should be some sort of security involved.

“We can’t keep going the way it is now,” Underwood said.

Asked what the solution is to the current situation at Pu‘uhonua O Waianae, Underwood replied: “That’s a great question.”

There’s plenty of finger-pointing going on between the homeless of Pu‘uhonua O Waianae and commercial fishermen and tour operators — who pay annual fees to use the harbor.

To prevent vandalism, the bathrooms are locked in the evenings and early mornings — when fishermen are most likely to need them. When they’re open, the bathrooms often are out of toilet paper and soap.

A commercial fisherman named Micah — who pays $75 in annual harbor user fees — was preparing to launch from the harbor for a day on the ocean last week but stopped long enough to say he regularly sees homeless people using the harbor’s water to wash their clothes and dishes and haul jugs of drinking water back into the encampment.

“They shouldn’t be allowed to run up the water bill that we’re paying for,” Micah said. He and other commercial fishermen asked that only their first names be used, fearing retaliation.

In January 2016, DOBOR received a water bill from the Honolulu Board of Water Supply for $5,827 for about 1.2 million gallons of water usage at the harbor.

In January, 2017, the bill had shot up to $19,169 for about 3.9 million gallons of water.

“As the camp grows, the bills grow,” Underwood said.

Naomi Seu, 63, has been living in Pu‘uhonua O Waianae with her dog, Charlie, for three and a half years and regularly rinses her clothes from a boat ramp faucet right where tourists climb aboard fishing, diving and snorkeling boats.

“I’m only rinsing because we’re not supposed to wash here,” Seu said as she twisted the water out of her clothes while Charlie lounged nearby. “Some of these boats — all kine rich people. They think they have more rights to the water than us local people.”

Tourist Theresa Salsberry, 49, of Des Moines, Iowa, saw Seu and Charlie earlier in the women’s bathroom as Salsberry and her husband, Kevin, 48, waited to board a dolphin tour boat.

“She was in the bathroom with her dog and she was talking to herself while washing something in the sink,” Theresa Salsberry said. “There wasn’t any soap so she offered me some. I said, ‘No thank you.’”

Number of residents unclear

No one can even agree how many people are living at Pu‘uhonua O Waianae.

In September 2016, a hui of 17 nonprofit groups and state and federal agencies for the first time collectively reached out to offer an array of services to the homeless residents. At the time, Borge told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser that the encampment included 289 occupants — including 48 children — and 147 dogs.

In a December report to the state Legislature, the Hawaii Interagency Council on Homelessness wrote: “The Pu‘uhonua O Waianae camp has … been in existence for over two years and its census has fluctuated from a high of 319 to a low of 170 individuals. … There is significant disagreement in the current estimated size of the Waianae camp, which DLNR estimates to be at 210 individuals as compared to 170 individuals reported by the camp residents. … DLNR reports that the cost of the water bill for the Waianae Boat Harbor alone now exceeds the revenues generated by harbor fees that are charged to harbor users and collected to cover utility costs. … In 2016, DLNR staff visited the property and found that a number of rock terraces that were previously identified as cultural resources are no longer in existence. Biologists with the DLNR Division of Aquatic Resources also are concerned that the encampment is adversely affecting the rare anchialine shrimp that live in ponds on the property.”

William Aila Jr. has a unique perspective on Pu‘uhonua O Waianae — as the boat harbor’s former harbormaster, as the former head of DLNR and as a current Waianae resident.

He respects the efforts of Pu‘uhonua O Waianae residents such as Borge to keep the encampment organized. Borge is often called the “mayor” or “governor” of the encampment, but Hokoana — Borge’s cousin — said, “We all call her ‘mamas.’”

Borge was not at the camp during a visit by the Star-Advertiser last week and did not respond to repeated phone calls and texts to her cellphone.

Despite what the Hawaii Interagency Council on Homelessness reported to the Legislature, homeless people have been living on the DLNR land next to the harbor since at least the 1980s, Aila said.

“The population has probably doubled since then,” Aila said. “For a few years, nobody (homeless) was in the harbor but in the late 1990s, early 2000s people started trickling back. That’s when Twinkle took over. I told them they needed to respect the place. I said, ‘If it’s not managed, I would push for a cleanup.’ She has done a decent job of maintaining the place without any government support.

“The trash pickup, the water, the use of the restrooms, and all of the missing toilet paper and other materials — it’s unfair to the boaters to be paying that burden,” Aila said.

But Aila does not want to see the camp swept without a designated place for the occupants to go.

“The overall homeless situation is tough,” he said. “We have to address it and treat people with respect on both sides.”

Hokoana said that any efforts to sweep the encampment would be met with fierce resistance.

“We’re going to protect this place,” she said. “We’re going to stand and fight.”