‘Golden Hill’ a twisty tale of potential colonial con man

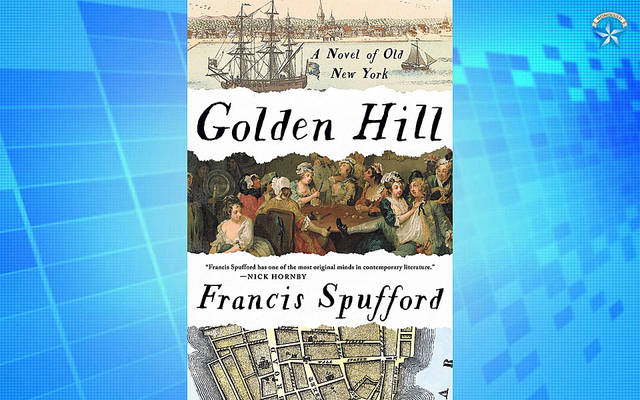

COURTESY SCRIBNER

“Golden Hill: A Novel of Old New York,” by Francis Spufford.

“GOLDEN HILL: A NOVEL OF OLD NEW YORK”

By Francis Spufford

(Scribner, $26)

“Seeming, seeming!” a Shakespeare heroine exclaimed as another character betrayed her. The novel “Golden Hill” is also about seeming, and its characters allude often to Shakespeare.

Everyone in this novel has a secret, and nothing is as it seems.

The story begins with Londoner Richard Smith arriving in New York City one rainy night to cash a note. The trouble is, the Colony has little in the way of hard currency, and the merchant whom Smith asks to cash the note can’t even be certain the note is genuine.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Plus, the amount of money in question is tremendous, enough to break the local economy should Smith turn out to be a con artist. Everyone in town wants to know: Is Smith a fraud, or is he for real, and if for real, to what purpose does he intend to put all that money?

Smith deliberately keeps everyone guessing, refusing to reveal his purpose, which the novel suggests is nefarious.

Small hints emerge. Smith has taught music and dance, hardly the occupations of a gentleman. He seems inordinately familiar with the theater and not at all familiar with sword fighting. He seems unusually observant of the slave Zephyra, who likewise seems unusually observant of him.

The novel follows Smith into a tavern for his daily breakfast (rolls and coffee), into the rooms of the governor’s spymaster, onto the roofs of New York’s houses, down to the docks, into a duel, onto the stage, into a high-stakes card game, and into private chats with a marriageable young lady.

The duality of each character is best exemplified by the face of the governor’s spymaster, which exhibits “the glazed patience of a porcelain owl.”

His face is like enamel, like an egg, blank, smooth, giving away nothing yet absorbing everything. In fact, each character’s appearance obscures his or her true purpose. The reader might discard one character as superficial, only to learn later his depth of personality.

Better even than the pounding plot is Francis Spufford’s writing. “New York is but a gullet,” one character observes. “Few stay.”

Or, “The judge’s real eyelashes were a sandy pink, like bristles in pigskin.”

Or, “Clinton’s peanut forehead creased anxiously.”

In short, Spufford knows his way around a metaphor or two. Other writers stumble when they use such imagery, but Spufford’s are clean and bright, concise and cutting.

In this Colonial world, Spufford has his details at the ready, revealing them to the reader on an as-needed basis, as with cards in a gambling game.

Men wear wigs and underneath they have … stubble.

Bathing is done with an pitcher, a basin and a rag, rarely in a tub and never in a shower.

Money is counted in English guineas, shillings and pence, but also Mexican dollars, Portuguese cruzeiros, Dutch guilders, Danish kreutzers and denominations minted and printed by each individual colony.

New York City weather is usually awful and the voices swirling around are likely to be in Dutch-accented English.

The plot offers twist after twist until the final one emerges, a wholly unexpected surprise carefully hidden from the reader in such a manner as to never raise suspicions. If the book has any shortcomings, it might be the last revelation, which doesn’t ring true, however much we might wish it did.

The reader can forgive this small slip in an otherwise perfect voyage in time, space and fiction.