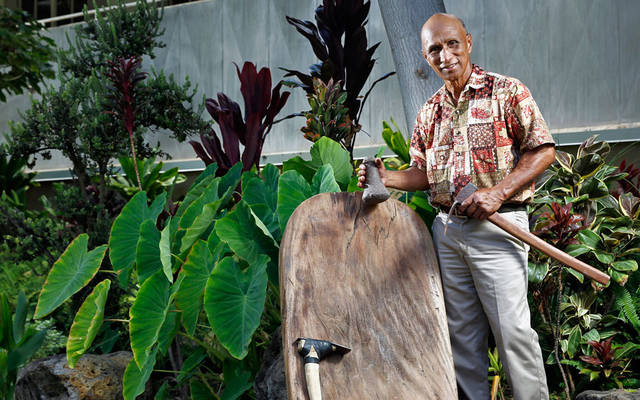

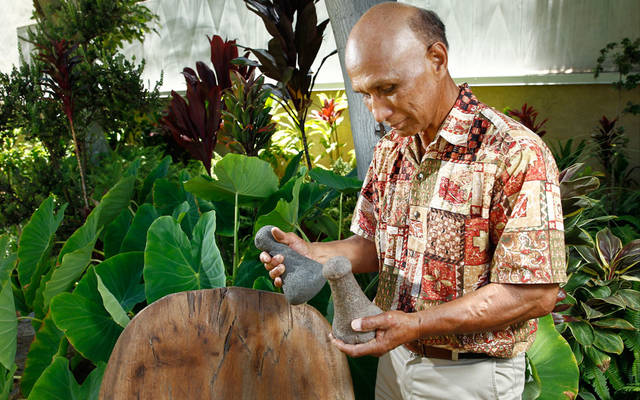

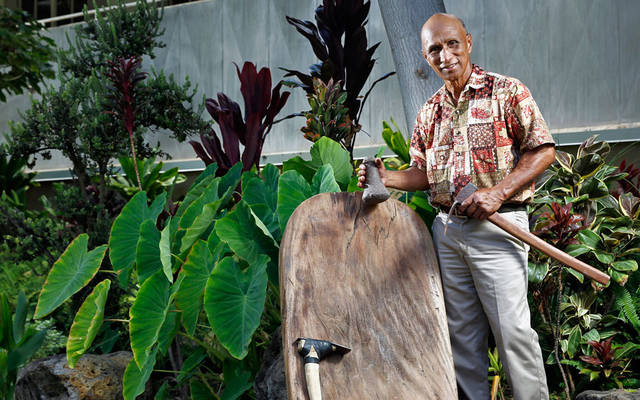

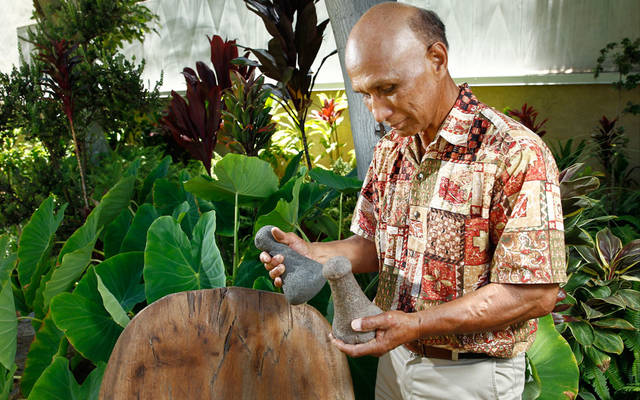

Earl Kawa‘a remembers a time when just about every family on his home island of Molokai owned a traditional handmade wooden board and pounding stone for turning taro into poi. So when Kawa‘a, 72, was getting ready to return to Molokai about 10 years ago to share the practice of pounding poi with younger generations, he made a dismaying discovery.

“I called my friends on Molokai that I knew pounded poi and had boards, and I could only get two boards and two stones,” he said. “Two boards and two stones. On Molokai. This is the land where I’m from in a community that I knew 90 percent of the families pounded poi. It broke my heart.”

Some quick thinking — and compassionate TSA agents at the airport in Honolulu — resulted in Kawa‘a hand-carrying 15 boards and stones from Oahu to Molokai, and the poi-pounding workshop continued as planned. The experience motivated him to pursue additional opportunities to share his knowledge of the once-common household practice.

In 2010, Kawa‘a, a Hawaiian resource specialist for Kamehameha Schools, made a TedX presentation in which he coined the phrase, “A board and stone in every home.” He’s since partnered with Oahu nonprofit Keiki O Ka ‘Aina to teach classes where families learn to make their own board (papa kui ai in Hawaiian) and stone (pohaku kui ai) from raw materials.

“This is the stuff you can’t find in books,” said Kawa‘a. “I teach them how to carve boards, but I’m also shaping attitudes and behavior for lifelong learning. The baseline is Hawaiian culture.”

TEACHING DIFFERENTLY

Kawa‘a, a Vietnam War veteran who holds a master’s degree in social work, points to his upbringing in remote Halawa Valley on Molokai by two pure-Hawaiian parents as one of the main influences that shaped who he is and how he shares his knowledge with others.

“I come from a farm background,” he explained. His father worked long days to provide for the family, while his mother was the disciplinarian of the household.

“My mother was the hammer. But the hammer doesn’t work for many people. It doesn’t work in the office. So I try to change that mentality.”

In his job at Kamehameha, Kawa‘a spends the majority of his time with at-risk youth of Hawaiian ancestry. In recent years he’s worked with students at Castle High School in Kaneohe and Roosevelt High School near Papakolea. Along with sharing his board and stone skills, he has also taught the high-schoolers about traditional Hawaiian sailing canoes and medicinal practices, and how to build a thatched hale (house) from materials gathered in the surrounding area.

He said working with high school students allows him to constantly refine his teaching methods.

“I suffered under the traditional teaching system,” he said. “So when I teach, all those things that I didn’t like teachers doing to me, I don’t do that.

“I don’t tell the kids, ‘You’re late.’ I tell them, ‘Thank you for coming to class.’ That’s what works.”

Kawa‘a carries that mindset into his activities with Keiki O Ka ‘Aina, where he insists that participants respect his role as kumu and make the effort to embrace not just the practical information he’s sharing but also the family-first attitude he intertwines with each lesson.

“The Keiki O Ka ‘Aina classes are designed to make the board and stone, so that’s the physical result,” he said. “But it’s also about shaping attitudes and behavior for family unity and lifelong learning.

“What happens is there’s a change in attitude and behavior. They’ll say afterward, ‘It’s not what I came in for, but I’m walking away with a lot more than I expected.’”

PUNALUU WOODWORK

For nine weeks in March, April and May, dozens of families convened under a tent across the street from Punaluu Beach Park, where Kawa‘a and a handful of assistants led a series of board and stone classes. Since 2013, the classes have also been held in Waimanalo, Papakolea and Kalihi Valley.

According to Kawa‘a, the Punaluu workshop was the most popular yet, with nearly 400 families originally registered to participate. To determine which families were going to be truly invested in the class, he asked those who signed up to attend an informational session and complete a homework assignment of sorts.

“There were so many who registered,” he said. “By attending the orientation, they were able to get a full understanding by the end of that night what their responsibilities were. I also asked them to write a protocol, as in a prayer, and they had a date by which to submit it. If they didn’t send it in, I told them to wait until the next class.”

Kaneohe resident Joshua Yoke, 41, was one of those who completed the requirements and took part in the Punaluu class, in which his wife, Cara Lucey, and two stepchildren were guided through the process of using tree branches to create the handle for an adze, the tool used in carving a papa kui ai. After the family selected a raw slab of wood for their board, they were taken to the banks of Punaluu Stream to select stones they would later chisel by hand into pohaku kui ai.

“I didn’t know what to expect because I’ve never done anything like this before,” said Yoke, who is originally from New Mexico and has lived in Hawaii for nearly 20 years.

“Cara and I have been together for about five years now and this is pretty much the first ‘Hawaiian thing’ we’ve done together to learn about her culture. It’s brought the whole family closer together.”

Yoke described Kawa‘a as “the salt of the earth” and the main conduit for connecting his family with the land and water they drew upon to provide the materials needed for their board and stone. As the weeks went by, Yoke realized he was getting more out of the experience than just practical knowledge.

“I thought we were just gonna learn how to pound poi,” Yoke said with a smile. “After the first class, it was all over. Kumu makes me feel like I can accomplish anything. I don’t really have the vocabulary to describe how he makes me feel. He just makes me feel at home.”

FAMILY MEN

The participants’ realization that the workshops are about more than just learning how to make a board and stone is what Kawa‘a counts on. Once that connection is made, he generously provides more opportunities for his “graduates” to continue their journey toward increased cultural awareness and family bonding.

“It’s more than just board and stone. It’s about confronting the challenges you have in life and facing them,” said Kawa‘a. “Board and stone is the baseline. From there, I take them onto other topics. I also teach how to carve canoe by hand. I’m teaching hooponopono (conflict resolution) classes, classes for dads to write mele inoa (name chants), songs for their daughters.

“It’s about strengthening families, since so many are being pulled apart. I make a concerted effort to get dads to do more in keeping the family together.”

Keiki O Ka ‘Aina will hold additional board and stone classes in the coming months. Call 843-2502, email contact@koka.org or visit koka.org/event/calendar Opens in a new tab for more information.