Thurston Twigg-Smith, a scion of missionary descendants who helped make the once-weaker Honolulu Advertiser Hawaii’s dominant newspaper, died Saturday at the age of 94.

Twigg-Smith served as publisher of The Advertiser from 1961 to 1993 until his Persis Corp. sold the newspaper to the Gannett Corp. But everyone from governors to copy boys referred to him simply as “Twigg,” said former Advertiser Editor Gerry Keir.

Under Twigg-Smith’s control, he and the late Advertiser Editor-in-Chief George Chaplin were credited with bringing the newspaper’s parochial and ultraconservative reputation more in line with Hawaii’s multicultural readership.

“Before Twigg took over, the paper had been stridently right-wing, anti-statehood, sometimes racist, too close to the haole elite,” Keir said. “Anti-union editorials ran on the front page. The paper once advocated tuition for public high schools to inhibit ‘stuffing book knowledge’ into local kids.”

A key moment for The Advertiser under Twigg-Smith’s leadership came in 1962 when the paper endorsed U.S. Senate candidate Daniel K. Inouye over Republican Ben Dillingham, whose father, Walter, was on The Advertiser’s board of directors at the time.

Walter Dillingham resigned from the board in protest.

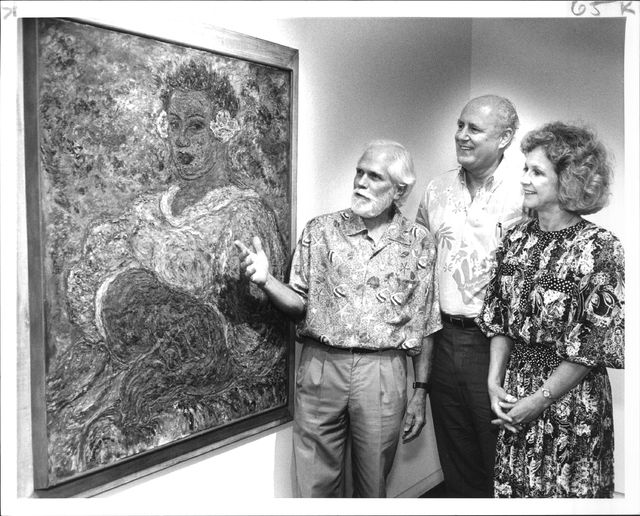

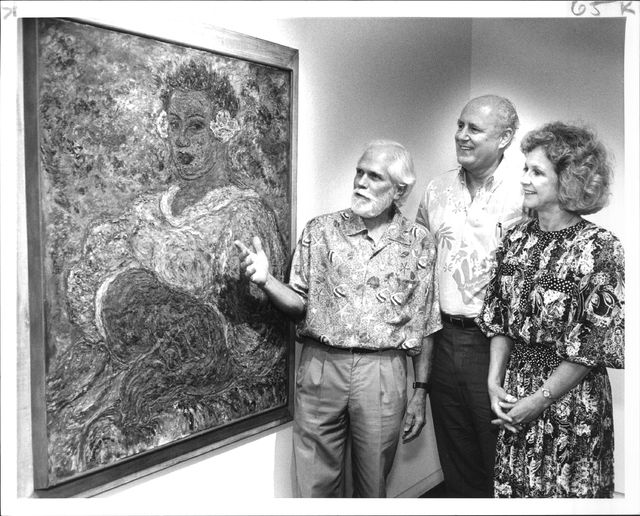

In the decades that followed, Twigg-Smith continued to acquire admirers, critics and plenty of contemporary art by local artists — which he proudly displayed throughout The News Building on Kapiolani Boulevard that housed The Advertiser, and later its longtime rival, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin. He also was the key figure in creation of The Contemporary Museum.

Twigg-Smith owned “the world’s most complete and most valuable collection of stamps and postal history of Hawaii,” Chaplin wrote in his book, “Presstime in Paradise: The Life And Times of The Honolulu Advertiser 1856-1995.”

Twigg-Smith’s collection included the “Parisian Murder” stamp, an object that Life magazine once called “the most valuable substance on Earth.”

Twigg-Smith — whose grandfather, Lorrin A. Thurston, helped orchestrate the overthrow of the Hawaiian kingdom — also collected plenty of critics when he wrote a 1998 book entitled, “Hawaiian Sovereignty: Do The Facts Matter?”

Barbara Hastings, a former science writer at The Advertiser, edited the book and her firm, Hastings & Pleadwell: A Communication Company, oversaw the book’s production, distribution and promotion.

“At the time he was writing an occasional commentary on the Hawaiian sovereignty issue from the point of view of a missionary descendant and grandson of Lorrin Thurston,” Hastings remembered. “He was troubled by what he saw were negative and distorted things being said of his grandfather. He decided to put his thoughts and research into a book, thinking that even if it didn’t attract attention at the moment, it would become part of the record for future historians and he hoped would bring more balance to the story.

“He was open to discussing his book and the issues with anyone and boldly participated in panels that might have intimidated a lesser man,” Hastings said. “There were a few times that were unpleasant, as I recall, but Twigg always was respectful of others and I never saw him get angry in the discussions. … I believe that Twigg has been a major factor in the business and economic community of Hawaii through the last half of the 20th century; however, I think that his role is discounted by those who did not find his book politically correct.”

Twigg-Smith, a fifth-generation scion of island missionaries, was born in Honolulu on Aug. 17, 1921.

After serving in several campaigns in World War II, Twigg-Smith came back to Honolulu to work for the family business run by his uncle, Lorrin P. Thurston, and served in every department The Advertiser operated, including a stint as the paper’s managing editor.

The Thurstons had owned The Advertiser since 1899 and Twigg-Smith engineered a takeover of company stock in 1961 to oust his uncle — a maneuver that his uncle never forgave him for.

As a businessman, Twigg-Smith was credited with saving the weaker morning daily newspaper by entering into a joint operating agreement with its larger afternoon rival, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, in 1962.

The Advertiser reportedly had less than a week’s worth of operating cash on hand at the time, but did own The News Building that in March 1963 became the headquarters for both competing newsrooms when their noneditorial operations merged into a third entity, the Hawaii Newspaper Agency.

“The papers combined ad sales, printing and delivery functions while retaining two fiercely competitive newsrooms on opposite sides of the News Building. … That brought money for more reporters, newer presses,” Keir said. “The community benefited as rival teams of larger reporting staffs competed to dig out the news.”

Keir called Twigg-Smith “the best kind of family newspaper owner.”

“He left Chaplin and his staff free to cover the news wherever it led,” Keir said. “It surely made for some uncomfortable mornings when Twigg picked up his Advertiser and discovered a friend’s name on the front page.”

The Advertiser crusaded against faulty school fire alarms, uncovered government purchasing scandals, spotlighted racism at the Pacific Club, got inside the secretive Family Court and shamed legislators who absconded with ‘Iolani Palace office furnishings, Keir said.

Advertiser editorials campaigned against high-rises on Diamond Head and for construction of the USS Arizona Memorial, a new concert hall — and a rail transit system that today has yet to become reality.

Former Advertiser Managing Editor Mike Middlesworth called Twigg-Smith “an excellent newspaperman and as fine a person as you can imagine.”

Under Twigg-Smith, The Advertiser lost 9 cents on every newspaper it delivered to the neighbor islands, but “he felt it was important for Hawaii to have a statewide newspaper,” Middlesworth said.

The Advertiser backed all-state sports teams and the statewide spelling bee, and Twigg-Smith personally participated in around-Oahu relay races and joined legendary Advertiser columnist Bob Krauss in circumnavigating the neighbor islands on foot — adventures that Krauss chronicled in his columns.

“He felt The Advertiser should be a major contributor to the community,” Middlesworth said. “As far as I’m concerned, that’s the thing that people should remember about Twigg: He was really interested in having the newspaper be a major factor of the community.”

In 1988, champagne broke out in The Advertiser newsroom when the morning paper finally surpassed its evening rival, the Star-Bulletin, in circulation.

By 1993, with combined annual profits topping $60 million, Twigg-Smith’s own heirs showed no interest in taking over the family business, and Twigg-Smith sold The Advertiser to Gannett.

When Gannett Co. sold the Star-Bulletin to Liberty Newspapers Limited Partnership in 1993 to buy the morning Advertiser, the Star-Bulletin’s daily circulation was about 88,000 and the Advertiser’s was approximately 105,000.

In June 2010, The Advertiser merged with its longtime rival, the Honolulu Star-Bulletin, to become the Honolulu Star-Advertiser.

Although he had sold the paper years earlier, Twigg-Smith retained an affectionate interest in its fortunes, Keir said.

He told Keir in an email that The Advertiser’s demise as a separate publication was “a terribly bleak occasion,” Keir remembered.

Twigg-Smith is survived by his wife, Sharon Twigg-Smith of Honolulu; daughters Margaret Fivash of Sequim, Wash., and Evelyn Twigg-Smith of Waimea; sons Thurston Twigg-Smith Jr. of Barnard, Vt., and William Twigg-Smith of Barnard, Vt. and Honolulu; stepsons Nathan Smith of Honolulu and Gabriel Smith of San Diego; 16 grandchildren; and 11 great-grandchildren.

A celebration of life is scheduled at 10 a.m. Aug. 27 at Thurston Chapel at Punahou School.