Review: ‘Pelicans’ offers challenging view of social misfits

‘Pelican’ was written by Eric Yokomori, directed by Taurie Kinoshita, set design by Justin Fragiao, costumes by Dusty Behner, lighting by Cora Yamagata. With Brandon DiPaola (Yully), Will Ha‘o (Abe), Randall Galius Jr. (Grandy), Jonathan Saavedra (Reno), AustinSunderman (Bentley), Eric Jabari Combs (Boy Hercules), Domina Hoffman (Papaya), Lisa Ann Katagiri Bright (Mom), Jeremy Reynon (Wiles), Gabriel Ramirez (Dilton).

They talk big, comparing themselves to the warrior Achilles of ancient Greece, but the boastful, foul-mouthed characters at the heart of Eric Yokomori’s timely and disturbing “Pelicans,” now playing at Kumu Kahua Theatre, are light years away from being heroes. They’re small-time, tragicomic boyz in the hood: idle, broke, disaffected but looking for meaning in their lives.

They resemble descriptions of the terrorists in the Brussels attacks. And indeed, when these rebels find their cause, all hell breaks loose. Until then, the would-be gangstas pass the time telling stories and good-naturedly insulting one another with obscene language and gestures. Their adolescent dirty dissing is so unrelenting, their conversations so filled with ugly profanity that if it were a film, “Pelicans” would easily rate an “R.”

The action opens as Yully (Brandon DiPaola), in headphones, jeans and sneakers, struts into a space framed by the exposed brick walls and peeling paint that lend a European ambience to courtyards in Honolulu’s Chinatown.

“Jobs is for punks,” Yully says to Abe (Will Ha‘o), a genteel natural aristocrat wearing a “Will work for food” sign. Yully gives the much-older man a cigarette, lights it — and calls him a bum. He could be insulting a future version of himself.

After shooing Abe away, Yully is joined, with greetings of “Yo, dawgs” all around, by the truculent Grandy (Randall Galius Jr.), a bloody tissue up his nose, and gluttonous Reno (Jonathan Saavedra), gobbling a burger.

Enter Bentley (Austin Sunderman), a bespectacled white boy in an Aussie outback hat who offers pizza in his campaign to join the gang. Although they’re hungry, the three young men of color decline: “We ain’t eatin’ no wankster pie.” After all, they say, Gandhi couldn’t be bribed.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

“Word,” they add for emphasis, as they do repeatedly throughout the play.

>>Where: Kumu Kahua Theatre, 46 Merchant St.

>>When: 8 p.m. Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays, 2 p.m. Sundays, through April 24

>> Cost: $5-$20

>>Info: kumukahua.org, 536-4222

Note: Talk story with playwright Eric Yokomori and cast following Friday’s performance

Written by Eric Yokomori, directed by Taurie Kinoshita, set design by Justin Fragiao, costumes by Dusty Behner, lighting by Cora Yamagata. With Brandon DiPaola (Yully), Will Ha‘o (Abe), Randall Galius Jr. (Grandy), Jonathan Saavedra (Reno), Austin Sunderman (Bentley), Eric Jabari Combs (Boy Hercules), Domina Hoffman (Papaya), Lisa Ann Katagiri Bright (Mom), Jeremy Reynon (Wiles), Gabriel Ramirez (Dilton). Running time: 75 minutes. Play contains explicit profanity and violence.

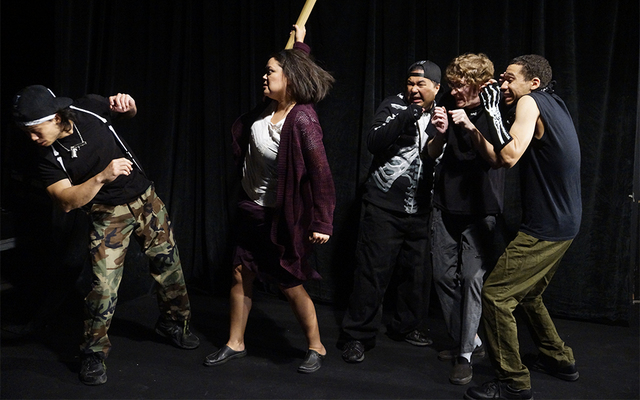

Joking turns to violence as Grandy strikes Bentley. A revenge plot is set in motion, with a twist: When Bentley’s mom (Lisa Ann Katagiri Bright) attacks, Grandy refuses to defend himself, saying real men don’t hit a “b——.” As the enraged mom beats him senseless onstage, the audience cringes at every blow.

These boys are desperate to be men but lack real-life role models except for Boy Hercules (Eric Jabari Combs), busy pimping fake watches and his girl, Papaya, played by Domina Hoffman, whose kewpie affect and comic timing steal the scene.

The absence of fathers makes it particularly moving when, in the play’s climax, Abe bestows a tender blessing on Yully.

With the excellent direction of Taurie Kinoshita and eloquent acting — including Jeremy Reynon’s portrayal of the mellow Rastafarian Wiles and Gabriel Ramirez as Dilton, the butcher’s assistant who delivers a tragicomic soliloquy on slaughtering cows — the characters register as individuals, not types. Yet as with all tragic heroes, hubris blinds themso that their dismay and surprise at what they’ve done is pitiable.

But the play provides no clue where this action is set. The characters talk ghetto slang, but are they residents of inner city Chicago or Los Angeles, or Hawaii hip-hop fans? If they live here, it seems incredible that they’re saving up to get a “ride” so they can go to the beach, where they’ve never been; nor are there any pelicans in Hawaii.

The titular birds aren’t discussed. Perhaps martyrdom is implied; the pelican, once believed to pierce its own breast and feed its young with its blood, is a symbol for Christ. But without any references in the script, the audience is unlikely to get it.

The mission of Kumu Kahua Theatre is to develop work that presents local subject matter, so when an actual Trojan horse, however cute, is randomly rolled onstage at the end of the play, it leaves the viewer feeling confused and frustrated about where this is happening and what it’s supposed to mean.

Still, while veering between bewildering and overly explicit, “Pelicans” challenges Honolulu audiences to confront the global societal malaise that overlooks and marginalizes young people with poetry in their souls. Billed as an “absurdist parable,” this violent, funny and profane play — like the genre’s groundbreaking “Ubu Roi” — aims to skewer the whole world.