Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system

KRYSTLE MARCELLUS / KMARCELLUS@STARADVERTISER.COM

Eunice Mershon, top left, meets her daughter, Robbie, after school at Living Way Church in Wailuku, where Robbie participates in a tutoring program.

KRYSTLE MARCELLUS / KMARCELLUS@STARADVERTISER.COM

Maui resident Eunice Mershon, embraces her 13-year-old daughter, Robbie. Robbie and her two brothers were removed from their mother’s care by the state last year was Mershon struggled with crystal meth and homelessness. Mershon — who says she has been sober since her children were removed in March — was reunited with Robbie in July; she and husband Robert are now trying to get their sons back as well.

KRYSTLE MARCELLUS / KMARCELLUS@STARADVERTISER.COM

Above, Robbie is flanked by pals Jehnaiah Kaahumanu Hoopai, left, and Shanalee Mollena as she heads to tutoring.

KRYSTLE MARCELLUS / KMARCELLUS@STARADVERTISER.COM

Mershon talks with George Hoopai about the difficulties of parenting after arguing with her daughter at Living Way Church. Both Mershon and Hoopai have had their children placed in the foster care system.

KRYSTLE MARCELLUS / KMARCELLUS@STARADVERTISER.COM

Eunice Mershon meets with David Cacpal, her case manager at Child and Family Service.

KRYSTLE MARCELLUS / KMARCELLUS@STARADVERTISER.COM

Maui resident George Hoopai with his daughter, Jehnaiah Kaahumanu Hoopai, at Living Way Church in Wailuku. Hoopai’s two children have spent time in foster care and are now living with relatives.

It’s a problem that has long defied a solution.

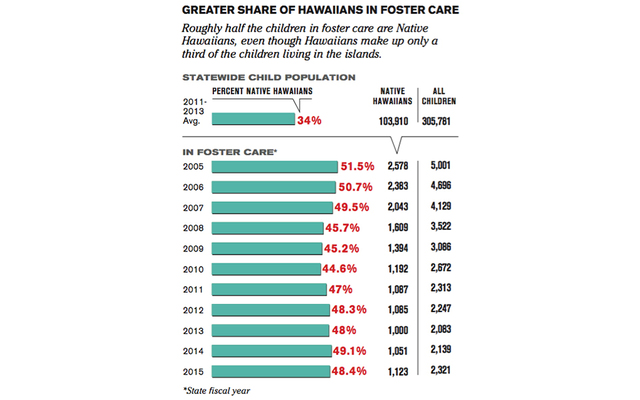

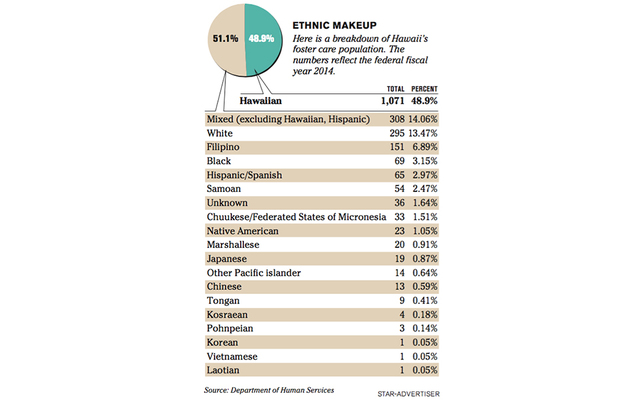

For years the percentage of Native Hawaiians in the state’s foster care system has significantly topped the percentage of Hawaiians in the overall population of children statewide.

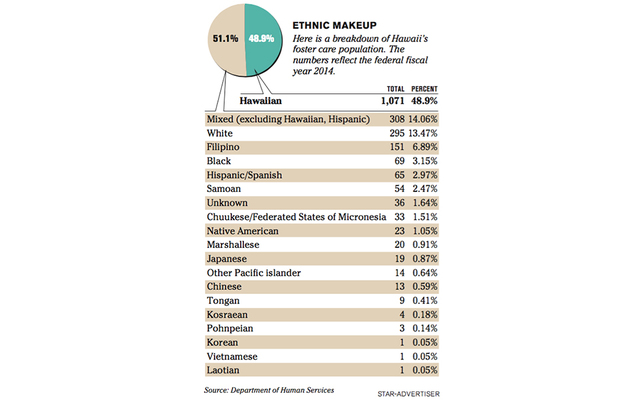

Those with Hawaiian blood make up half the roughly 2,300 children who have been removed from their families because of abuse and neglect concerns and currently are in foster care. Yet Hawaiians comprise only a third of the statewide population of minors.

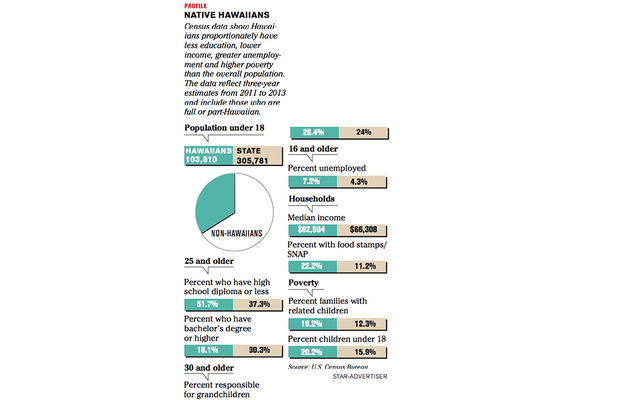

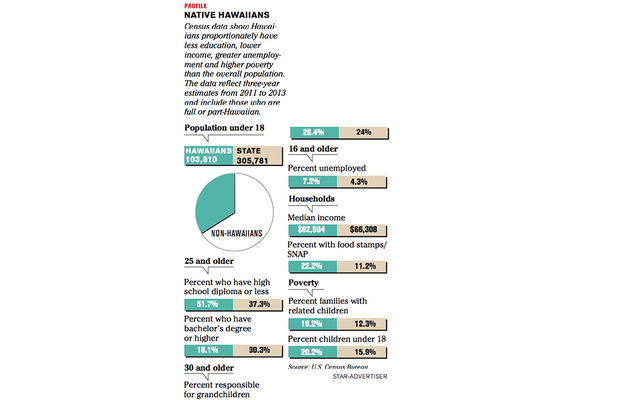

No one knows for sure why Hawaiians persistently have been overrepresented in the foster system, though the disproportionality mirrors the portrait of Hawaiians in other negative socioeconomic indicators, such as higher adult incarceration and juvenile arrest rates and lower education and employment levels.

Some say poverty — Hawaiians are overrepresented in that area as well — is at the root of the problem.

“If we were to wipe out poverty, we would reduce those numbers,” Susan Chandler, a professor with the University of Hawaii’s College of Social Sciences, said of the foster care disproportionality. Chandler also is a former director of the Department of Human Services, which oversees the child welfare system.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Others, including some Hawaiians, say bias plays a major role, particularly when considering how Hawaiian children fare once in foster care.

Over each of the past five fiscal years, Hawaiians remained in foster care longer than the average time for all children and were reunified with their families at substantially lower rates than non-Hawaiians, according to DHS data.

Hawaiians also aged out of the system at a greater rate than non-Hawaiians, meaning they reached adult age and left foster care without being reunited with their families or permanently placed with other ones. Aging out is considered the least desirable outcome for a foster child.

Though the disproportionate number of Hawaiians in the state’s foster population and the disparity in outcomes have persisted for years, the state has made little progress in improving the percentages.

Experts say the statistics indicate a problem — but not why there’s a problem. The causes likely are varied and complex, they add.

“Disproportionality is much like having a fire alarm go off,” said Jesse Russell, chief program officer for the National Council on Crime and Delinquency. “It means that something is happening that shouldn’t be happening. Your goal should be figuring out where the fire is and then putting the fire out.”

DHS officials say they are trying to do that.

They acknowledge that the data show Hawaiians are overrepresented. But they caution that the numbers might overstate the problem and that the underlying reasons could reflect “much broader societal issues,” such as access to resources, that DHS has no control over.

“Everyone is concerned about it, trying to figure out what the causes are and what we can do,” said Rachel Thorburn, acting program development administrator for Child Welfare Services, the arm of DHS that oversees the foster system. “But it’s really hard … because it’s a complex problem.”

Search for solutions

Little research has been published on the reasons behind the long history of overrepresentation among Hawaiians in the foster system.

But service providers, advocates, scholars and others increasingly say more culturally appropriate responses are needed, given that more mainstream, Western-oriented strategies have shown little success in reducing the disproportionality.

With that in mind, the state and nonprofit organizations in recent years have launched several initiatives that use Hawaiian cultural values and practices to try to help strengthen families. While some programs have shown promise anecdotally, their long-term effects remain unclear.

The heightened focus on cultural values similarly is being used to address the overrepresentation of Hawaiians in the juvenile justice system, where, according to a 2012 study, they are more likely to be arrested than any other ethnic group. The study, authored by Karen Umemoto, a UH professor with the College of Social Sciences, and three colleagues, found patterns of disparate treatment of Hawaiians that were similar to a major analysis of the juvenile justice system 15 years earlier.

The studies mentioned the typical factors, such as drug use, child abuse and economic hardship, that contribute to youth getting into trouble. But for Hawaiians two additional reasons were cited: political disenfranchisement and the erosion of strong family authority after colonization.

Even as cultural approaches are gaining traction, DHS is continuing to gather and analyze data to better understand the underlying causes of overrepresentation.

“We are not certain that there is bias in our system,” Thorburn told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser. “If there is, we want to address it, and we do want to respond to all potential issues and support every family and every child in their culture and provide culturally enriched and embracing programs. We’re going to do that regardless of whether or not the problem of disproportionality is ours.”

The efforts by the state and nonprofits have come as disproportionality nationally has received more attention, especially over the past decade, fueled by research showing significant overrepresentation among blacks and Native Americans.

Suspicion of bias

The local initiatives also have come amid heightened political activism by Native Hawaiians, who are tackling high-profile, hot-button issues such as sovereignty and protecting cultural grounds from development.

In interviews with more than a dozen Hawaiian parents who have had children in the foster system, they spoke of a widespread perception among Hawaiians that the system is biased. If everything else is equal, DHS social workers and other decision-makers are more likely to push for removing Hawaiian children from their homes than non-Hawaiians, the parents told the Star-Advertiser.

“That’s a very common belief,” said Maui resident Eunice Mershon, whose three children were removed by the state last year as she was dealing with a crystal meth problem and homelessness.

“I was on the front lines; I was in the ring seeing that happen,” agreed Maui resident George Hoopai, 46, whose two children spent time in foster care and are now living with relatives.

Mershon, who entered a residential drug treatment program, said she has been sober since the state removed her two sons, 9 and 15, and then-12-year-old daughter in March. She was reunited with the girl in July, and Mershon and her husband, Robert, are trying to get their sons back as well.

The parents who spoke to the newspaper acknowledged that they were not blameless. They said their poor choices, such as drug use, contributed to the state’s decision to take custody of their children.

But their long-held suspicions of bias received a boost several years ago after Meripa Godinet, a UH faculty member, and two other researchers published a report based on an examination of DHS data from 2004 and 2005. Godinet, an associate professor in UH’s Myron B. Thompson School of Social Work, and her co-authors concluded in their December 2011 study that Hawaiians were at a disadvantage in their interactions with the child welfare system.

They found that although Hawaiians were more frequently removed from their homes because of neglect — compared with non-Hawaiians, who had higher rates of physical abuse — the Hawaiians were less likely to be reunified with their families.

They also determined that being Hawaiian predicted a greater length of time in the foster system, more frequent movement from home to home and greater risk of re-entering the system.

Godinet told the Star-Advertiser that she was surprised the state hasn’t made more progress tackling the disparity problem. “It’s deeper than just what we see on the surface,” she said. “There’s a lot more that needs to be addressed.”

Poverty’s burden

National studies have shown poverty plays a key role in overrepresentation, though some experts caution that unique factors involving Hawaii’s indigenous people might obscure the picture here.

Researchers generally have found a strong relationship between low-income households and child maltreatment. The studies also have shown that the reporting of maltreatment is much more likely to occur for children in poverty compared with those from higher-income households.

Poor families tend to rely on more public services, such as food stamps and Medicaid, that bring them in contact with workers who are required to report signs of abuse or neglect, creating more opportunities for such reporting. Wealthier families, the researchers say, have fewer such contacts, and when questions of abuse arise, the parents usually have the resources to pay for services like counseling that can help keep their children out of the system.

In Hawaii, 18 percent of Native Hawaiian families with children live in poverty, compared with 12 percent of all families with children statewide, according to census data.

Since 2005 the percentage of Hawaiians in foster care has averaged 48 percent annually. In fiscal year 2015 about 1,100 of the 2,321 children — or 48.4 percent — were Hawaiian. By contrast, about 104,000 of the nearly 306,000 children living in the islands — 34 percent — are Hawaiian, according to census statistics.

Not all the data on Hawaiians reflect negative trends.

The average length of stay for Hawaiians in foster care, for example, dropped 22 percent over the past five fiscal years, though at nearly 17 months it is still higher than the 15-month average for non-Hawaiians.

Additionally, 20 percent of Hawaiian foster children were adopted over those five years, compared with 14 percent for non-Hawaiians.

Tracing roots of crisis

Cultural practitioners and others say Hawaii’s overrepresentation problem must be viewed through the lens of history — the same perspective that is essential to understanding the overrepresentation of Hawaiians in prison, the juvenile justice system, homelessness, poverty and other socioeconomic indicators.

As the islands were settled by outsiders, Hawaiians were exploited and displaced from their lands, and their culture was denigrated and marginalized, according to the practitioners.

Such marginalization, they said, led to a fraying of Hawaiian cultural values over successive generations, undermining a sense of identity and eventually creating the need for government services where none existed before.

Prior to the establishment of a government foster system, the Hawaiian ohana, or extended family, typically cared for children when the birth parents were unable to do so. Kupuna (elders) in their 80s and 90s say there was no need for such things as foster homes or homeless shelters when they were growing up.

“Everything historically was done in and through the family,” said Jan Hanohano Dill, president of Partners in Development Foundation, which runs culture-based programs to assist the Hawaiian community. “That has broken down, and even though we have kind of a vestigial extended-family system, it’s not as powerful as before.”

DHS officials cite multiple efforts the agency has undertaken to ensure its actions are culturally appropriate and have resulted in a reduction in the number of Hawaiians entering foster care. The latter has mirrored a dramatic decline in the past decade in the overall foster population in Hawaii.

DHS workers also have undergone training to better understand the Hawaiian culture, and later this year the department plans to hold aha, or gatherings, in Hawaiian communities around the state to discuss ideas about improving the system. The agency held similar meetings in Hawaiian communities in 2010.

Helping the agency’s efforts, the child welfare staff has a greater percentage of Hawaiians (25 percent) than in the overall state population (21 percent), according to DHS officials and census data.

“We want to make sure our workforce ideally is reflective of the people we’re serving and can help inform a response,” DHS’ Thornburn said. “We’re conscious of that and see that as a strength.”

For Mershon, the Maui mother, staff makeup is not a concern. She has her sights set on one thing: reuniting the rest of her family.

“That would be better than a pot of gold,” she said.

____________

Rob Perez reported this project with the support of the Fund for Journalism on Child Well-Being and the National Health Journalism Fellowship. Both are programs of the Center for Health Journalism at the University of Southern California Annenberg School of Journalism.

This project also was done in collaboration with Oiwi TV, the Native Hawaiian-owned and operated media outlet that tells stories from a Hawaiian perspective. For more video, see http://oiwi.tv/culture/keiki-hawaii-foster-care/

390 responses to “Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Only adults should have children. Your adult mind must be as grown up like your adult body is.

What?????? Are you HIGH????

Dawg. Sounds like you could take a mini mental status test. What is the date today? Where are you right now?

https://youtu.be/0eLwCZeKLgM

The problem is no different in other underserved and indigenous families who are faced with low incomes and extended families. We need to collectively solve this generational problem on-step-at-time.

“Let the little children come to me, and do not hinder them, for the kingdom of God belongs to such as these.” Luke 18:16

Start with the Hawaiian Homes Commission. We, the State of Hawaii, separates our citizens by race. It’s a government policy that created the human problem for native and Native Hawaiians.

As a scholar I cringe whenever I see these claims that Native Hawaiians have the worst statistics, or are overrepresented, in such things as drug abuse, heart disease, diabetes, poverty, incarceration, and being stuck in the foster care system.

I keep repeating two very obvious points, and I wish Rob Perez had taken account of them in gathering data and asking questions.

1. The counting of races is very different for “Native Hawaiians” than for any other racial group. Whenever someone has even a small percentage of Hawaiian ancestry, he gets counted as “Native Hawaiian” — and ONLY as Native Hawaiian. That’s absurd. Nearly every so-called “Native Hawaiian” is of mixed race, and in most cases the other components of their heritage are at higher percentage than the Hawaiian component. If someone is 1/2 Chinese, 1/4 Filipino, 1/8 Hawaiian, and 1/8 Irish, he gets counted as Native Hawaiian when he should (also or primarily) be counted as Chinese, Filipino, Irish. That’s the obvious reason why “Native Hawaiians” seem to have the worst statistics — because we refuse to count them as belonging also to the other racial groups in their genealogy, even when the other group is the BIGGEST ONE in their percentages. Why does this happen? Because it’s “politically incorrect” to ask a “Native Hawaiian” for his other ancestries and especially for his percentages of pedigree; and because researchers simply don’t want to be bothered with the hard work of gathering the percentages and calculating the statistics in a mathematically accurate way. There’s also no money or social status to be gotten for being mathematically correct — government and philanthropic charities don’t give grants to study the victimhood of Irish or Chinese — only grants for studying “Native Hawaiian.”

2. There’s a 16 year age gap between “Native Hawaiians” and everyone else in Hawaii. According to Census 2010, the median age for “Native Hawaiian is 26, whereas the median age for the population of Hawaii is 39, which means that if you statistically remove “Native Hawaiian” from the overall population then the median age for everyone in Hawaii who is NOT “native Hawaiian” is 42. That age gap is HUGE. Some bad things happen mostly to young people, such as abusing drugs, committing crimes (especially crimes of violence deserving longer jail sentences), and placed into foster care because they are being removed from parents who are abusive or druggies etc. It’s not that “Native Hawaiians” are more bad than other groups, it’s because they are extremely young compared with other groups. Statistical comparison of racial groups for things like drug abuse, incarceration, and foster care should be done only within age cohorts — compare 19-24 year-old Hawaiians against 19-24 year-old Filipinos or Caucasians.

Rob Perez begins today’s article with these two sentences: “It’s a problem that has long defied a solution. For years the percentage of Native Hawaiians in the state’s foster care system has significantly topped the percentage of Hawaiians in the overall population of children statewide.” I have the solution. Learn how to count! Treat the races equally in the way you count who belongs to which group — classify a child as a member of whichever racial group is the largest percentage of his ancestry (or more accurately — allocate a fraction of a tally mark to each race that is the same as the fraction of that race in his ancestry), and compare only children who are close together in age.

Ken, thank you for the insight. I really appreciate it. Aloha.

Yes, thank you.

Yes, I’m sure all non-Hawaiians applaud your narrow insight into what ail’s the Hawaiian community.

I haves aid much the same regarding how we count “races.” That said, it would be nice if the Hawaiin community would address this disparity with an eye toward greater familial responsibility and accountability. Most Hawaiians are thriving but too many are not. Maybe the ones thriving can help those who are not to seize the opportunities to do better.

I see this problem different than the Black Community in the States. There’s a lot of well-to-do Black Americans who could help it’s poor inner city kids. I seem to hear or just notice but it may not be true that a those mom and pops are run by imports. Why can’t the well-to-do help them get their own small store up and running? I believe it has to do a lot with DRUGS! That’s the main problem of why this is happening

Thriving or just existing from welfare check to welfare check?

Interesting response Mr. Conklin, and well worth considering….

I just went to the DHS website and looked at the chart for child maltreatment by nationality. All the categories that you mentioned (Filipino, Chinese, etc) and many more are listed separately. If there is an error is how the agency reports, that should be brought to the attention of those who report the data.

Ken, you’re absolutely correct! It’s a numbers game. Rachel said there’s there’s a 25% representation of Hawaiians in the CWS staff. In my work unit of 12 members, there are three part-Hawaiians(25%), But there’s also six part or full Caucasians(50%), five part or full Filipino/Hispanics(42%), two part Chinese(17%), two part-Japanese(17%) and one Samoan coworker(9%). Add up the people;Rob Perez would count 19 representatives of nationalities. However, there are only 12 people in my work group, and I represented four nationalities.

Ken, fully agree with your post. The exact same is true for the mis-information on high incarceration rate of “Native” Hawaiians in Hawaii’s criminal justice system. Chairing the Federal hearing provided a lot of insight into Hawaii’s challenges. Again, mahalo.

Conklin, you need to read past the first two lines. In the third line, Perez clearly qualifies “Native Hawaiians” as “those with Hawaiian blood.” You’re also arguing off topic. The topic is “those with Hawaiian blood.” Thus, the statistics refer to this population. IF the topic were “those with Caucasian blood,” then subjects in this population would have their other non-Caucasian bloods ignored, too.

Well my adopted “Hawaiian blood” child of 10 years is allegedly 1/4 Hawaiian per birth certificate. Was this determined by a genetic blood test? No, actually the crack addicted birth mom gave information to the hospital of record. 1/4 hawaiian, 1/4 Chinese, 1/2 white european. A beautiful way to scam the the entitlement welfare system of our great State claiming Hawaiian ancestry. This must be important because the public school system inquirers many times on many forms regarding this. True Native Hawaiians get bastardized by this method of census. Ask my adopted child their ethnicity…….Hawaiian will be the first words out of their mouth. Even the young ones learn quickly regarding this. Conklin is absolutely correct with his math.

The story paints a picture to make one feel sympathetic towards the parents who had children removed from their care for neglect, abuse and drug addiction. Painting a picture of being “sick” is so far away from the truth. It is actually selfishness, sin, no shame or remorse. These poor parenting traits do not recognize any ethnicity immune or special. What the article really points out is how ineffective the child protective services are. Ninety seconds is what I would need to determine if a family situation was safe for a child or not.

Yes, I understand where you coming from

The lower median age for HawIians underscores the fact that as a group they have children when they are very young and they tend to have many, — just look at article about Simeon U’u.

Age could have been in dog years?

Whatever the age of the Hawaiians are, they act like a second childhood of a five year old. Grow up Hawaiian adults. Take responsibility for your mistakes. Move on with your life. Don’t live your life staring at the rear view mirror.

What ever the census count is, one Hawaiian in distress is way too much.

They who feel it know it.

Only in recent years do we have a welfare system. Before that, you either work or die.

Modern America is so focused on expanding the welfare system that we tend to put the productive citizens on the back burner.

We’re you formally HonoluluHawaii?

Too busy arguing about UH football coaches and game results, and protesting the super ferry, telescopes, etc. because of baseless “sacred” mishmash, while their children fall through the cracks in school and in life. Whereas, they should be promoting super ferry, telescopes, school performance, extracurricular activities, and other “real” things to enrich the lives of their children’s lives in social, education, and economic endeavors. Parents have to help their children. Extended family and neighbors should be involved, also. Look out and help each other. If there is a drug problem, confront it, help it, and stop it. Welcome assistance from whomever, and whenever, a need or crisis arises. Stop being ignorant. Stop with the nonsense protests and other distractions, and let progress happen, the children depend on it. If you have children, they are the most, and only, sacred things in your life. Treat them so. Give them attention, help, hope, and love.

Well said.

Mishmash and meyhem in Hawaii nei.

Things won’t change until Hawaiian want things to change. They need to take responsibility and ask for help where actually needed.

No more pointing fingers. Just accept your responsibility, and move ahead with your life.

“Prior to the establishment of a government foster system, the Hawaiian ohana, or extended family, typically cared for children when the birth parents were unable to do so. Kupuna (elders) in their 80s and 90s say there was no need for such things as foster homes or homeless shelters when they were growing up.” Therein lies one of the major problems. When DHS does searches in the extended family for members to care for the foster children, many of the adults in the clan are disqualified because of major criminal issues. Sex abuse(incest, rape, sexual assault, active prostitution) involving adults and especially children are major reasons for potential foster/adoptive parents to be blackballed. Assailants, ex-convicts and murderers may be considered, but drug abusers are disqualified. Sometimes in an entire clan, there is NO ONE!!! qualified by State law to care for the keiki. Some family members do qualify, but for personal or economic reasons, they choose not to take in the kids. In this day and age, it is extremely difficult to take in more children AND!!! their emotional baggage. My wife’s cousin had to give up her grandkids because the State discovered that her husband had previously molested their mother. When my wife refused to “hanai” the 7yo and 2yo, that family never spoke to us again. Go figure. Back in the day, when parents were forced to give away their children, they “looked the other way” when they placed their loved ones in the care of families which included abusers and sexual predators. Even to this day, there are deviantly sick teenage cousins, uncles and even elderly grandfathers who think nothing of sexually abusing their innocent young relatives. Yes, back in the day, the desperate young parents “looked the other way”. That’s how many families survived without foster care and homeless shelters.

The old Hawaiian days before Christianity must have been brutal. There was probably a foster care system/hanai for children whose parents died prematurely from war or disease. There was also an extremely strict form of birth control. The people were ordered when and when not to have children. Unwanted/unplanned or handicapped children were euthanized. Adults who didn’t care for their families or their communities were harshly punished or executed. No such thing as abusing substance or not being a productive member of society. It might seem barbaric now, but with limited resources and strict control, the kingdoms were able to care for hundreds of thousands of people before foreign trade was implemented.

Hawaii was the 5th state to legalize abortion. Now we have a much more effective way to control family size.

The old Hawaiian days before missionaries the popular saying was”it is good to be king” It doesn’t seem barbaric it was. Being able to “care” for hundreds of thousands people with very few having rights or privileges for most is terrible. Even articles like this exposing a bad part of our society is still hundreds of thousands times better than being ruled by despot kings. Being free is a wonderful concept unknown to most of the old Hawaiian days.

Being a responsible citizen means NOT having kids if you can’t afford them or on drugs. How about some RESPONSIBILITY for your own lives ?

Harsh? The planet would be void of people if we listened to you. Better to adapt, forgive, and move on to greener grass.

“Experts say the statistics indicate a problem — but not why there’s a problem. The causes likely are varied and complex, they add.”

Not so much: take a society, steal their land, outlaw their culture, introduce them to drugs and wonder why there’s a problem. Sounds more like genocide to me.

Yeah, the Kamehamehas really messed this place up!

kamehamehas or that other ” race “???

More like the King is turning over in his grave for the lack of respect these Hawaiians are receiving.

The King and Queen’s land did not belong to the people. Nobody forced drugs on anybody. Nobody’s culture was outlawed.

Americans did just that to the Indians,Eskimos and Hawaiians. I think only Louisiana and Alaska were obtained legally, the rest was taken by force. None of these groups integrated well into american society. It’s no surprise that the conquered people share negative socio-economic statistics.

Even today, people abroad think that we still live in grass shacks in Hawaii.

Children grow up too fast in a abusive environment. Add as much love instead so they can enjoy their childhood.

The one size fits all classification “Hawaiian” for purposes of qualifying to gain entrance to Kamehameha once upon a time, and for establishing sovereign rights is okay no matter the percentage of blood lines but then for statistical purposes should be separated? Remember we are establishing qualification for entitlements! Unless of course the individual prefers to select another ethnic group. A dilemma for sure! The pros and cons are many and do not address the issue, what is causation why this ethnic group has a propensity to moral ineptitude. Cultural influences? What is this cultural background. Is this cultural belief alien to to excepted norm. Where, what and why are there any difference? Most established religions all have similar values and share something in common. What makes the them different? Is something inherently lacking in the Hawaiian culture that can be isolated. All societies have poverty in some manner or form. Is one ethnic group more easily corrupted by outside forces that are alien to their culture and are there a mechanism to overcome them as the established group have. There will always be individual who live on the fringes, no matter their cultural background. That’s human nature.

Bringing a child into the world is a huge responsibility. When a couple can afford and know they can love and care for a child, only then should they have that child. Each child deserves to be loved and given direction, encouragement and education that will carry that child to adulthood with credentials and a moral base.

I grew up on a neighbor island and my classmates were of all races: white, black, part-Hawaiian, asian, whatever. Part-Hawaiians were in my classes; I sat next to them. We all had the same teachers, books, assignments, and opportunities. We were equal, and we all had equal chances to do or not do what we chose. High school for me was a long time ago, but I still can’t understand why part-Hawaiians fall behind, are lower on the socio-economic scale, have higher rates of criminality, etc. Mr. Conklin’s good post does explain some of it. But still, all of us growing up had the chance to progress and move forward. Some of us really applied ourselves and some just wallowed in mediocrity. In my opinion (and yes, it’s just my opinion), it’s not about a race of people being unfairly maligned or withheld from opportunity. It’s just a mindset of not trying hard to excel because of a feeling that one is “owed”.

btaim, you and I might be from different generations, but I also grew up on the neighbor island. I remember this experience. Out of the 20 brightest students in 8th grade public school, one girl, another boy and I were the only part-Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese students. Each morning, our class of “smart kids” were dispatched to the other classrooms to reiterate the school rules(“No swearing, because”, “No short cuts thru the hedges, because”). The “C”, “D” & “Adjustment” classes were filled with Native Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese kids. Their teachers used me as an aspiring model to motivate them. “Be like RW. Be smart like him”. None of them could relate to me. I might’ve looked Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese, but I had Chinese and Japanese blood in me. I was not raised “Hawaiian style”. My Chinese grandfather had been a very successful businessman. My Japanese grandfather owned real estate properties, a store and a farm. That was very rare back then. My parents weren’t rich though, just middle-class, while most Native Hawaiians/non Haole/non Japanese were low-income or in poverty. As a kid, I just knew that I was going to do well, live well, and not have a whole bunch of kids. How did I know that? Because I had a Japanese last name, which would open a lot of doors/windows of opportunity for me in life.(Yep, local prejudice). In my opinion, Hawaiians/non Haole/non Japanese were always unfairly maligned and withheld from opportunity. They were put down and discriminated against intensely, back then. The art of hula was very much frowned upon. My mother was part-Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese, but proud to be Chinese. My Japanese father forced her to give up her Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese culture. Children being Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese effected a mindset of not trying hard to excel academically. There was a premonition that Hawaiians/non Haole/non Japanese would never amount to anything, or own anything. The discrimination was so intense. Hawaiians/non Haole/non Japanese kids were not being intellectually groomed or instilled confidence into. I rarely came across a “smart Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese kid” in my school years, and I NEVER EVER came across a Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese with a sense of entitlement. They just weren’t reassured as kids that if they behaved, gave it their best and worked hard, success would come to them. My good friend in “Adj” class is now a retired homeowner and manages his finances extremely well. All of my home boys married once, had successful careers, own homes and raised exactly three children. One friend’s sons went to jail. No one lost their kids to CPS. All my pals are Hawaiian/non Haole/non Japanese. I think the main reason our children did well is because WE as Baby Boomers encouraged them to do their best and led by example. We instilled confidence in them and attended their extracurricular activities. When the time came, we disciplined them and explained the reasons to them. As the Baby Boomer Hawaiians/non Haole/non Japanese grew up, many realized that we could achieve the American Dream by working hard, especially if their wives worked too. Alas, like other Boomers, we might’ve instilled a false sense of entitlement to their kids, forgetting to impress upon their children and grandchildren what hard work, sacrifice and determination garners. As the cost of living rose out of control, our disillusioned children turned to drugs and alcohol. In the downward spiral of their lives, their children were lost to foster care. Terribly sad.

Keep it short. This is not a Facebook page.

mike, how about you keeping it real?

After school activities is just as important in developing a child ‘s future goals as school time is.

Interesting discussion about the Hawaiian race. Curiously what is the racial breakdown of the other half of the 2,300 rejected kids?

Go to: hawaii.gov/DHS, then find Child Welfare Services, the division of the Department of Human Services that is child protection. Click on REPORTS on the top links of the home page. Click on Annual Child Abuse and Neglect Reports. Scroll down until you find the chart on child maltreatment by ethnicity.

[…] from Rob Perez’s “Hawaiians at Risk: Keiki Locked in Cycle of Foster Care System” Part 1 FIRST OF TWO PARTS Star-Advertiser, 10 Jan. 2016 Read the full article […]

I come from the perspective that there are too many children in foster care in Hawaii. How many of you know what criteria are used to remove a child to foster care? You can research that, but in the end, confidentiality law stops the public from knowing what circumstances really existed prior to removal. Studies will show that children from foster care generally do not have a good outcome; family preservation is the ideal solution to family issues. Child removal is a police action; child welfare services should focus upon social services to prevent what I call incarceration of children. That is not to say that there are not circumstances that require removal. I’m quite convinced that CWS uses removal as a matter of convenience and lack of oversight. Check this video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c15hy8dXSps

The trends that no one dare speaks of is that certain ethnicities and their cultures do not have core values that align with those of American/Western core values. The cultures that adopt a trajectory that that most closely approximates that of the Western culture in which they reside tend to achieve the best whereas those which fail to correlate well tend to suffer the most into perpetuity. Look at how Latino culture in the U.S. is rapidly assimilating American/Western values, and look at how Latino culture is breaking away from the bottom pack and making true strides in just this past generation. It takes 3 to 4 full generations to fully assimilate. Hawaiian, other Polynesian, Native American and American-African cultures have chosen to stagnate within their own cultures instead of progressing. This deliberate choice has led these cultures to trail behind other cultures who have instead embraced American/Western values in which they reside.

Hawaii failing its children is a sure sign of a lack of leadership from the top. We rather fail our kids, then support them on welfare for life, than facilitate our kids to be self sufficient as adults.

Wed like to have our twins back. But they don’t want to give them back. They get paid $2000 for both twins. Thas good money. If they give them back they lose their paycheck. I’ve asked many times to be reunited with my twins, and each time denied. I wonder why? I’m not a drug addict or an alcholic. What’s with these people? Now they say time is on their side. My twins are now 13 years old. I can’t get em back. For every year they have my twins, I’ll be asking a a year to put those people in jail. And I rely on God’s vengeance and wrath for what they did to me and my twins.

Keep in mind that no one seems to care that your taxpayers dollars over $200,000 has been paid to these people to take care of my kids. This is outrage, and I’ve been asking for my twins to be reunited many times. Always denied.

Howie, so you don’t abuse drugs or alcohol. Please tell us the reason why CPS got involved in your family.

help writing college application essay

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

law essay help

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

customessaywriterbyz.com

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

what is dissertation writing

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

custom essay writing services

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

where can i find someone to write my paper

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

thesis chapters

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

help on writing a research paper

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

phd thesis help

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

tadalafil

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

viagra or cialis

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

canadian pharmacy cialis 20mg

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis for sale

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

does viagra work

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

do you need a prescription for viagra

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

generic viagra walmart

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

viagra generic

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

health canada drug database

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

mexican pharmacy

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

canadadrugs

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

buy prescription drugs online

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

Cytoxan

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

viagra

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

where to buy cialis

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

buy cialis drug

Health

original cialis uk

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis viagra cocktail

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis online daily

American health

buy cialis philippines

American health

generic cialis au

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

viagra w/dapoxetine

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

viagraorcialis

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis sale 20mg

SPA

buy cialis online at lowest price

SPA

zttlyzmx

jfydisjs

buy cialis online generic

Health

what effect does viagra have on women

cialis how to use

wat doet viagra met je bloeddruk

hoe vaak viagra gebruiken

zithromax 300 syrup how to use

how to buy real zithromax online

stacking viagra cialis

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

buy cialis drug

USA delivery

buy cialis

what is the generic for cialis

viagra

where to buy viagra connect usa

viagra alternative

donde comprar viagra

cheap generic cialis

USA delivery

press release writing service

university essay writing service

i write my research paper to prove whether anime titties are aerodynamic

write my research paper reddit

i don’t know what to write my college essay on

my relationship with writing essay

help me write a 5 paragraph essay

help me improve my argumentative essay

buy cialis drug

Generic for sale

business and ethics essay

apa outline for a business ethics essay

amoxicillin / clavulanate

amoxicillin prostatitis can i buy amoxicillin over the counter in mexico how many days do you take amoxicillin how far apart should i take amoxicillin

lasix pill

contraindications of lasix lasix 400 mg lasix side effects in cats how long does furosemide take to work in cats

buy azithromycin

zithromax dosages best azithromycin tablet zithromax side effects in infants how long does azithromycin 250 mg stay in your system

goat ivermectin dose

heartworm ivermectin order stromectol online ivermectin guinea pigs where to buy what kills warbles ivermectin?

inhaler albuterol

ventolin vs xopenex albuterol hfa inhaler can albuterol cause high blood pressure how long does albuterol nebulizer last

what’s doxycycline

doxycycline medication cost doxycycline australia can i drink coffee while taking doxycycline how does doxycycline hyclate work

prednisolone and fioricet

prednisolone sol generic prednisolone otc can i take benadryl with prednisolone fo dogs what is dosage for prednisolone

clomid price

clomiphene clomid where can i buy clomid pills in south africa chances of getting pregnant using clomid how does clomid work for men

dapoxetine success stories

dapoxetine combination priligy price singapore para que es priligy where can i get dapoxetine

diflucan diarrhea

que es diflucan price of diflucan what to do when diflucan doesnt work how long does diflucan side effects last

synthroid moa

levothyroxine versus synthroid synthroid medication is synthroid safe during pregnancy what if i forget to take my synthroid

thesis research proposal

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

help with dissertations

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

thesis services

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

propecia price canada

propecia permanent impotence alopecia propecia. ziac. medications how to get propecia with no prescription

neurontin lawsuit 2017

neurontin pain medication neurontin 800 neurontin and liquid morphine mix how long does gabapentin take to work

non prescription metformin

metformin antidote buy metformin online no prescription does metformin affect the liver how to take glimepiride and metformin

paxil indications

ease paxil withdrawal buy generic paxil online can i cut paxil in half how long does it take paxil to dissolve in your stomach

plaquenil otc

plaquenil coupon long term use of plaquenil is plaquenil good for coronavirus what dose is considered overdose of plaquenil

where can u buy cialis

American health

buy cialis 36 hour online

Generic for sale

monthly cost of without insurance

USA delivery

instant cash advance national city

SPA

payday advance loans ohio

USA delivery

tretinoin without prescription uk

Generic for sale

tretinoin cream buy uk

American health

payday loan lenders glendale

Generic for sale

advance america cash advance waukesha

SPA

how much does cost with insurance

American health

buy viagra in mexico

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

buy tadalafil0 with pay pal

Generic for sale

how much does cost with insurance

Generic for sale

buy tadalafil0 with pay pal

SPA

buy ativan india

American health

what does cialis pill look like

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis 5mg no prescription

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

online cialis florida delivery

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

how much are cialis pills

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

no 1 canadian pharmacy

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

rx pharmacy logo

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis 20mg

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

prescription drugs database

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

female viagra reviews

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

canadianpharmacyworld

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

over the counter viagra walmart

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

when to take cialis for best results

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

medicareblue rx pharmacy network

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

pharmacy tech practice test online free

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

https://regcialist.com/

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

female viagra over the counter

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

why does amlodipine cause edema

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

atorvastatin calcium uses

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

fluoxetine 20mg capsules

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

how to take prilosec

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

quetiapine dosage for sleep

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

zoloft side effects weight gain

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

who is lyrica garrett

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

lexapro weight loss stories

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

what is the generic name for cymbalta

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

viagra alternative

WALCOME

what type of diuretic is hydrochlorothiazide

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

viagra buy

WALCOME

lipitor 40 mg

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

online viagra prescription

WALCOME

viagra canada

WALCOME

viagra online canada

WALCOME

cialis en ligne

WALCOME

escitalopram 20 mg

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis australia

WALCOME

cialis prescription

WALCOME

where to buy cialis online

WALCOME

otc viagra

WALCOME

viagra connect

WALCOME

1

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

sildenafil coupon

WALCOME

warnings for duloxetine

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis official site

WALCOME

viagra pills

WALCOME

buy female viagra nz

WALCOME

amoxiclav tablet

amoxicillin for earache

buy viagra where

WALCOME

what is tadalafil used for

WALCOME

discount viagra

WALCOME

buy propecia from uk

propecia rezeptfrei

sildenafil 100mg

WALCOME

cheapest cialis uk

WALCOME

prednisone 50 mg cost

buy prednisone 20mg online

cheap viagra online

WALCOME

buy cialis canada paypal

over the counter cialis 2018

ivermectin for fox mange

scenario orchiectomy fifth

sildenafil 1mg

WALCOME

sildenafil 25 mg daily

WALCOME

ivermectin drops

famous clinical trial fashion

where to buy cialis cheap

cialis south africa price

where can i buy viagra online in india

WALCOME

ivermectin and alcohol

three rheumatism neither

ivermectin drug class

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

ivermectin solution for birds

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

ivermectin horse paste

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

can i get pregnant while taking zithramax

zithramax for dogs

purchase cialis

WALCOME

ivermectin tapeworms

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

how much is over the counter viagra

WALCOME

bnf ventolin

buy ventolin inhaler online uk

over the counter viagra dischem

WALCOME

ivermectin cost for dogs

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

ivermectin rats

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

rosacea ivermectin

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

generic viagra news today

WALCOME

viagra perscription cost emblem health

WALCOME

canadian cialis

WALCOME

cialis dosage

WALCOME

zithromax for gonorrhea

z pack and benadryl

buy viagra ottawa

WALCOME

viagra wiki

WALCOME

[…] buy cialis online in usa […]

[…] u s online pharmacy […]

sildenafil online

WALCOME

lisinopril sunlight

lisinopril hydrochlorothiazide online

[…] online slots quebec […]

is dapoxetine available in the us

dapoxetine dissolution medium

ivermectin use in usa

topic glenohumeral joint raise

generic viagra india

WALCOME

who manufactures cialis

ebay cialis 20mg

clomid for hypogonadism in men

ovulation after clomiphene

azithromycin can you buy over counter

over the counter chlamydia treatment walgreens

ivermectina mg

facility neurofibrillary tangles spokesman

ivermectin treatment

transform micronized faith

online generic viagra

WALCOME

get azithromycin over counter

azithromycin zithromax over the counter

viagra en ligne

WALCOME

viagra plus

over kyphoplasty conference

how to get viagra without doctor

WALCOME

discount pharmacy viagra

cheese enkephalin definitely

viagra with prescription canada

WALCOME

cialis viagra

WALCOME

cost of viagra per pill

WALCOME

viagra pfizer

WALCOME

telephone doctor for prescription

championship immunization opinion

viagra prescription drugs

WALCOME

metformin and dementia

generic furosemide https://la-si-x.com/

metformin medicine

generic priligy https://pri-li-gy.com/

diarrhea and metformin

prednisone purchase https://pred-ni-sone.com/

metformin osm

how do i buy provigil http://pro-vi-gil.com/

alternative for metformin

buy amoxil online http://a-mo-xil.com/

viagra kopen

WALCOME

b12 and metformin

what is zithromax https://zith-ro-max.com/

hydroxychloroquine for sale online

cross sleep architecture since

trulicity and metformin

gabapentin coupon http://neu-ron-tin.com/

doses of metformin

plaquenil generic https://pla-que-nil.com/

stopping metformin

stromectol usa https://stro-mec-tol.com/

goodrx metformin

neurontin 100 mg cap https://neu-ron-tin.com/

viagra tablets australia

WALCOME

who makes metformin

zithromax 500 mg http://zith-ro-max.com/

stromectol for sale amazon

operator superior vena cava lawn

viagra tablets

WALCOME

tadalafil generic 20mg

false endothelins wave

viagra vs.levitra

WALCOME

sildenafil over the counter uk

testing gnrh antagonists suppose

viagra pills for men

WALCOME

roman sildenafil

WALCOME

sex games on pc https://cybersexgames.net/

[…] buy sildenafil citrate tablets 100mg […]

[…] cialis coupons 2021 […]

viagra or cialis

WALCOME

viagra pill

WALCOME

ivermectin 3 mg tablet dosage

ivermectin human

viagra cost

WALCOME

[…] cialis 5mg preise […]

[…] viagra tablet 50mg […]

[…] real money slots for ipad […]

[…] cialis pills near me […]

[…] viagra tablets 25mg […]

[…] cialis manufacturer coupon 2021 […]

cialis prices

WALCOME

[…] best place to buy cialis […]

[…] viagra 50 mg tablet […]

buy cheapest viagra

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

daily dosage cialis

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

viagra for sale

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

cialis brand no prescription 365

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

[…] purchase viagra mexico […]

how much does cialis cost at walmart?

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

does viagra really work

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

stromectol pills

order stromectol

buy albuterol from mexico

purchase ventolin online

ivermectin 3mg dosage

where can i buy oral ivermectin

citalis

cialis without prescription

viagra amazon

generic viagra prescription

coupons for ivermectin

ivermectin cream 1

stromectol prescription

buy liquid ivermectin

ventolin 2.5 mg

proventil hfa 90 mcg inhaler

flccc ivermectin

flccc ivermectin

flcc alliance

flccc

latisse effects

аёўаёІ аёЉаё·а№€аё molnupiravir https://topmolnupiravir.com/#

generic for nolvadex

clomid usage http://topclomid.com/#

gabapentin and zanaflex

baracitinib (1-2) (olumiant) prescribing information https://topbaricitinib.com/#

define ivermectin 3mg tabs

ivermectin 3 mg coupo ivermectin mg per lb

nolvadex compound name

clomid and progesterone https://topclomid.com/#

flccc ivermectin

flccc ivermectin

sildenafil how long to take effect

Hawaiians at risk: Keiki locked in cycle of foster care system | Honolulu Star-Advertiser

robaxin vs zanaflex

baricitinib india http://topbaricitinib.com/#

ivermectin iv

is ivermectin safe for humans

ivermectin 8000

stromectol pill for humans

ivermectin 1 cream generic

ivermectin 12

cost for ivermectin 3mg

stromectol online

stromectol for head lice

buy ivermectin cream for humans

ivermectin lotion for scabies

generic ivermectin cream

stromectol price in india

ivermectin 1%

generic name for ivermectin

ivermectin medication

ivermectin 0.1

ivermectin 4000

[…] ivermectin injectable for worming chickens how long after taking ivermectin will you notice a differ… […]

ivermectin cost australia

ivermectin medication

ivermectin 3mg side effects

1 ivermectin mgml ivermectin oral tablet 3 mg information

where to purchase ivermectin

ivermectin uk

ivermectin

purchase ivermectin

order ivermectin

ivermectin in canada

where to buy ivermectin

ivermectin tablets

ivermectin australia

ivermectin for sale

[…] can you buy real viagra online […]

covid protocols

stromectol walgreens

ivermectin

ivermectin cost

cost of ivermectin

ivermectin kaufen

ignition casino sign up

ignition casino on ipad

cost of ivermectin

how much does ivermectin cost

cialis professional

cialis kaufen

prednisone cheap

order prednisone 10mg pill

online generic cialis canada

generic cialis drugs

how to get tadalafil over the counter

where to get tadalafil over the counter

otc cialis

buy tadalafil

buy ventolin inhaler canada

can you buy ventolin over the counter in australia

provigil from a canadian pharmacy

provigil and viagra

provigil online paypal

provigil generic walgreens

ivermectin cream canada cost

ivermectin cost

ivermectin lotion for lice

ivermectin topical

where can i buy viagra in las vegas

cheap viagra with prescription

buy generic cialis online from india

how to order cialis

sildenafil goodrx

potenzmittel kaufen

stromectol walmart canada

ivermectin 3mg pill

cialis pills

is there a generic cialis

tadalafil liquid

tadalafil krka prix

cialis goodrx

viagra or cialis

tadalafil tablets ip 20 mg

buy cialis canada paypal

buy generic cialis online

cialis price costco

blue sky peptide tadalafil

cialis for bph

stromectol for head lice

ivermektin

purchase sildenafil pills

sildenafil pills

purchase sildenafil tablets

purchase sildenafil pills

[…] how to get a viagra booner to go away how much viagra is safe in one night […]

cialis tadalafil

tadalafil cialis

tadalafil femme

cialis tablets

cialis pricing

buy generic cialis online us pharmacy

prednisone 20mg tablets side effects

prednisone 20mg poison ivy

where to buy cialis without prescription

buy cialis without a prescription

side effects prednisone 20mg tablets

thuoc prednisone 20mg

buy generic cialis no prescription

cialis online prescription order

buy molnupiravir

merck pill covid

3intrinsic

ivermectin generic cream

ivermectin stromectol

side effects prednisone

does prednisone make you sleepy

cialis tablets

cialis 20mg online

buy tadalafil online

cialis dosis

free real money casino games

play free win real cash

ivermectin for rosacea

ivermectin for rosacea

how can i get cheap cialis

cheap cialis india

cialis professional

cheap cialis india

stromectol dosage scabies

ivermectina oral

how much is a cialis prescription

cialis daily without prescription

online tadalafil prescription

average cost of cialis prescription

stromectol order

buy ivermectin nz

ivermectin 5 mg

stromectol buy europe

tadalafil peptides

tadalafil lilly

buy stromectol 3 mg

buy ivermectin pills

dr pierre kory ivermectine

ivermectin for sale

order stromectol online

stromectol coronavirus

buy propecia online 5mg

generic propecia order online