His dark battle

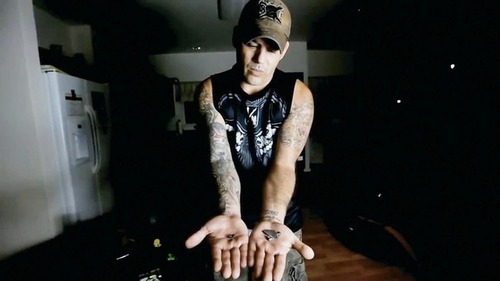

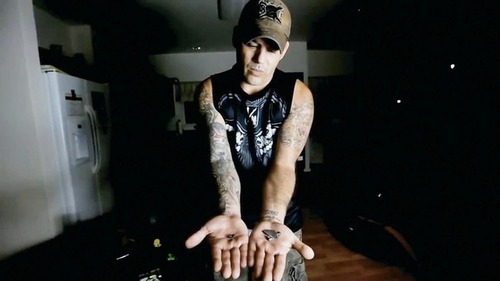

Courtesy Staff Sgt. Robert A. Ham Staff Sgt. Robert A. Ham's award-winning minidocumentary "Level Black -- PTSD and the War at Home" focuses on Staff Sgt. Billy Caviness, a Schofield Barracks soldier who developed post-traumatic stress disorder after he was badly wounded in Afghanistan two years ago. Caviness displays the shrapnel doctors removed from his body.

Billy Caviness wife, Tina.

Billy takes a number of prescription medications, above, and is in the Warrior Transition Battalion at Schofield Barracks.

In “Level Black — PTSD?and the War at Home,” Staff?Sgt. Billy Caviness and his wife, Tina, are honest in their description of Billy’s struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder.

Staff Sgt. Billy Caviness is on patrol — not in the mountains of eastern Afghanistan, where he was wounded in battle, but in his tree-lined neighborhood in Schofield Barracks.

The fight that he waged outside is now inside, in his head, on a deployment that never ends.

"I’m always worried about somebody coming in my house and hurting my family. But I’m always on guard, and I’m ready for anything at any time," says Caviness, a soldier for 17 years. "I used to be able to determine combat zone and home. But now, to me, everything’s combat zone."

Caviness’ experience with post-traumatic stress disorder — which has afflicted more than 250,000 veterans from the Iraq and Afghanistan wars — is chronicled in riveting candor in an 8-minute, 41-second minidocumentary put together by Staff Sgt. Robert A. Ham, a U.S. Army Pacific videographer at Fort Shafter.

There are no interviews with doctors or counselors, no "Army Strong" theme music. It’s mostly Caviness, at home, with his wife and kids, telling the unvarnished story of his inner struggle after mortars and rocket-propelled grenades blew holes in him and seriously wounded some of his soldiers in 2011.

"PTSD is no joke," Caviness says as he sorts through more than 12 prescription bottles on his living-room couch. "And if you got it, you’ll understand exactly what I’m saying."

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

As he talks, a scene inserted by Ham plays in the window behind Caviness of a .50-caliber machine gun being fired — as if the war still rages right outside his home.

"I think about my wife and kids," the soldier says at one point. "If it weren’t for my wife and kids, I could probably guarantee you I wouldn’t be here. My wife put up with a lot. I put her through hell, and she’s still here with me. Just shows how strong of a woman she is."

Caviness experienced sleeplessness for days on end and guilt over the injuries that befell his soldiers in the same attack in which he was seriously wounded.

Ham visited with Caviness’ family over a span of months in the spring and summer of 2012 to make the film. He was recently named the Defense Department’s videographer of the year for 2012, and his documentary on Caviness won first place in the features category.

He set out to put something together on Caviness as a Purple Heart recipient, but then realized that his fellow soldier’s ordeal with PTSD was a message that perhaps should be communicated with the public.

"As it started to evolve, I felt like, ‘I really want to try to communicate this as best I can to people who don’t understand (PTSD),’ and there are a lot of people who don’t understand," Ham said.

Caviness’ wife, Tina, describes her husband as being characterized as "level black," the worst of PTSD sufferers. The documentary is titled "Level Black — PTSD and the War at Home."

The soldier now is in the Warrior Transition Battalion at Schofield awaiting medical discharge with full benefits, the Army said.

Lt. Col. D. Bruce Beech, the battalion surgeon for the Pacific Regional Medical Command’s transition battalion, said 197 soldiers are assigned to the unit. Of those, 95 have PTSD.

Beech said most transition battalion soldiers have at least several significant medical conditions that can be physical and behavioral or neurological, including the aftereffects of traumatic brain injury.

According to a December Department of Veterans Affairs report, as of June 30, 2012, about 257,000 of 1.5 million Iraq and Afghanistan veterans had been seen for potential PTSD.

Tripler Army Medical Center was not able to provide information as to how many PTSD cases are being treated in Hawaii.

In his time in the Army, Caviness deployed to Bosnia, Kuwait, Iraq and Afghanistan.

It was with the 3rd "Bronco" Brigade out of Schofield in Afghanistan’s Kunar province in May 2011 that Caviness and his soldiers experienced a mortar, rocket-propelled grenade and small-arms fire attack at Combat Outpost Honaker-Miracle.

Caviness, who was unavailable for comment for this story, said in Ham’s documentary that he had a hole the size of his fist in his right thigh and his penis was split down the middle.

In the infirmary, he thought about the third child he and his wife wanted, but now he couldn’t have.

Things got worse.

"My whole world was flipped upside down. It done a 360," Caviness says. "I felt like I was useless. I had no job, I had no soldiers. I couldn’t function. I couldn’t think on my own, I couldn’t walk on my own, I had to have help in and out of the bathtub, on and off the toilet. One of the hardest things I’ve ever had to go through."

Caviness said he couldn’t sleep for days and he experienced hallucinations.

He said he was "constantly thinking about and seeing the faces of the soldiers that either passed on or got hurt severely. That’s an everyday struggle for me."

He asked his wife, on a scale of 1 to 10, where she thought he was at, and if he needed treatment.

"And I told him, truthfully and honestly, I said, ‘You are pretty much an 11 or 12. You really need to go (get help),’" Tina Caviness says in the documentary.

Five months after he got back from Afghanistan, he started treatment for PTSD.

He used to blame himself for his soldiers’ injuries, "but I also got to realize I was the first one to get hit, and I also got to understand and tell myself that it wasn’t my fault cuz I did everything that I could to keep my soldiers safe," he said.

Ham, the soldier who made the documentary, told Caviness to just "be honest."

Ham notes that Caviness has a lot of tattoos — including a helmeted skull on his shoulder — he swears a lot, and can be rough around the edges. In the film he favors "Metal Mulisha" shirts.

There may be a tendency to "pass him off — but he is the kind of guy that we need (and) that we call when we are fighting a war when we need warriors to get to the front lines and fight," Ham said.

Society shouldn’t dismiss those troops "because now that we have sent them to war, we need to make sure we take care of them when they get back," Ham said.

Caviness says it was "a really big help" being around other soldiers who went through similar situations. He added that his chain of command and the medical staff went above and beyond the call of duty on his behalf.

The Army said he still has a long road ahead. He still walks with a cane. He’s a little less on guard, but still feels the most comfortable at home.

Sgt. Maj. Kanessa Trent, a spokeswoman for U.S. Army Pacific, said the command is very proud of the documentary put together by Ham.

"Soldiers that experience post-traumatic stress have been exposed to experiences that most people can’t even imagine," Trent said. "So they are not crazy, and I think that is a misunderstanding. … So hopefully, stories like Billy’s and his family’s will help people understand that it’s dealing with horrors that are unimaginable."

There is one last bit of good news in Ham’s film. The final seconds show the Schofield soldier holding his new daughter, Annabella Mariah Caviness — the third child he never thought he’d be able to have — who was born Dec. 4, 2012.