Struck by scandal

Inouye, chairman of the Senate select committee probing the Iran-Contra affair, gestures to reporters in Washington that the day's session of the hearing would be cut short. Inouye decided to have Lt. Col. Oliver North return the next day after tempers began to flare during the questioning.

North, a Marine who wore his uniform and medals throughout the hearings, is sworn in by Inouye, whose back is to the camera. Inouye sported his Distinguished Service Cross lapel pin in a sly response to North's attire.

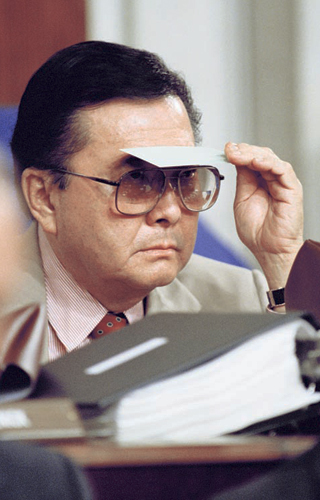

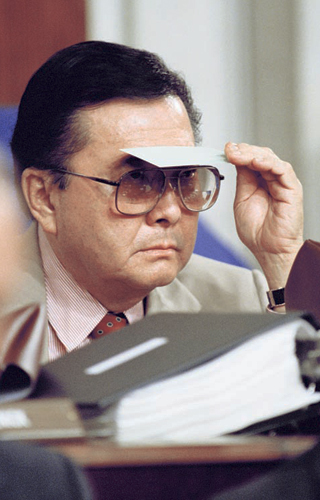

Inouye shades his eyes with a sheet of paper as Brendan Sullivan, North's attorney, speaks during the Iran-Contra hearing on Capitol Hill.

« Previous article: A trusted voice (6 of 9)

Inouye’s national prominence seemed to peak in the 1970s and 1980s. His name had surfaced as a possible vice presidential contender, but he would always dismiss any aspirations beyond the Senate, where he had friends and power.

He was becoming one of the Senate’s "old bulls" — conscious of its history and traditions, and protective of its intricate procedures and the value placed on seniority.

It was Inouye who took the uncomfortable but necessary job as advocate for U.S. Sen. Harrison Williams, a New Jersey Democrat, when the Senate sought to expel him after his bribery convictions in the Abscam scandal. Williams had been caught on videotape trading his influence for an interest in a titanium mine with an undercover FBI agent posing as an Arab sheik.

Inouye, who essentially served as Williams’ defense attorney on the Senate floor, said the Senate had only previously expelled senators for treason. Williams resigned in 1982 to avoid expulsion.

|

"It has had a major impact on my life, which has become a living hell." Don't miss out on what's happening!Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

By clicking to sign up, you agree to Star-Advertiser's and Google's Terms of Service Opens in a new tab and Privacy Policy Opens in a new tab. This form is protected by reCAPTCHA.

|

The entry on Inouye in the 1984 "Politics in America," a snapshot of the nation’s political landscape published every two years by Congressional Quarterly, said the senator’s "role in developing legislation has not matched either his seniority or his popularity."

But Senate leaders again came to Inouye with a politically sensitive assignment. He was asked to lead a select committee to investigate the Iran-Contra affair, a scheme by the Reagan administration to trade arms for Iranian-held U.S. hostages and use some of the proceeds from arms sales to help finance a Contra rebellion against the socialist Sandinista government in Nicaragua.

Like Watergate, the committee’s hearings were televised nationally and put Inouye in the spotlight. The committee found that Iran-Contra was "characterized by pervasive dishonesty and inordinate secrecy." The senator conducted the probe with grace and uncovered some damaging revelations, but the trail never quite reached President Ronald Reagan and the public’s verdict was much more indifferent than it was after Watergate.

Lt. Col. Oliver North, the telegenic Marine at the center of the scandal, wore his uniform and medals to the hearings and was a sympathetic figure to many Americans. As a sly counterpunch — and perhaps to remind viewers that he, too, was a patriot — Inouye wore his Distinguished Service Cross lapel pin.

Mike Royko, the legendary Chicago newspaper columnist, wrote that Inouye came across as an "inscrutable Buddha." But the senator scored when he publicly scolded North, who had admitted lying to Congress, for suggesting that lawmakers often leaked sensitive information. "I can also understand why North looked more subdued at that point than he has during the entire hearing," Royko wrote. "He knew he was being chewed out by a genuine hero."

Inouye’s higher profile from Iran-Contra would, like after Watergate, come with some backlash. The senator was criticized for inserting $8 million into a foreign operations bill to build parochial schools in France for North African Jews. Inouye had become among Israel’s most important allies in the Senate and had spoken against the historic injustices to Jews, so his support for the schools was not out of character. But it turned out he had received a $1,000 campaign contribution from a friend, New York real estate developer Zev Wolfson, who was on the board of the charitable group that would oversee the federal money going to France.

Inouye at first defended the appropriation as proper but later apologized and asked that the money be withdrawn.

The timing of his uneven reviews on Iran-Contra and the bad press on the Jewish schools was not ideal. Inouye, at 64, was interested in replacing U.S. Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia as majority leader after the 1988 elections. Senate Democrats were looking for a national spokesman — a fresher face who could communicate effectively on television — and while Inouye had a cadre behind him, they would choose U.S. Sen. George Mitchell of Maine. Mitchell, who led the party’s Senate campaign committee when Democrats took back the Senate in 1986 and had blossomed during the Iran-Contra hearings, won 27 of the 55 Democratic votes. Inouye and U.S. Sen. J. Bennett Johnston of Louisiana each had 14.

The leadership defeat was a disappointment to Inouye, but not nearly as personally painful as an episode that would soil his 1992 re-election campaign. His Republican opponent, state Sen. Rick Reed of Maui, obtained a tape recording of Inouye’s longtime hairstylist, Lenore Kwock, claiming Inouye had pressured her into sex in 1975 and later sexually harassed her.

Reed was criticized — by Kwock and the leaders of his own party — for going public with the steamy allegations in campaign advertisements. Inouye denied the claims and won re-election with 54 percent of the vote, the lowest victory margin of his career. But Inouye was stung when nine other women told a state lawmaker after the election that they were also sexually harassed by the senator.

Women’s rights groups asked for a Senate Ethics Committee investigation, while Inouye called the anonymous new charges "unmitigated lies." Kwock, who said she had forgiven Inouye, refused to cooperate with Senate investigators. The senator’s other accusers never came forward publicly, so the inquiry was dropped.

Inouye insisted the accusations had no impact on his effectiveness in the Senate, which was torn at the time by sexual harassment allegations against U.S. Sen. Bob Packwood, an Oregon Republican who would eventually resign in disgrace.

"But it has had a major impact on my life, which has become a living hell," Inouye told a local reporter.