Honor and loyalty

Inouye and his wife, Margaret, relax with their dogs and Inouye's parents, father Hyotaro and mother Kame. Inouye was one of four children born to Hyotaro and Kame, who raised the family in McCully and Moiliili.

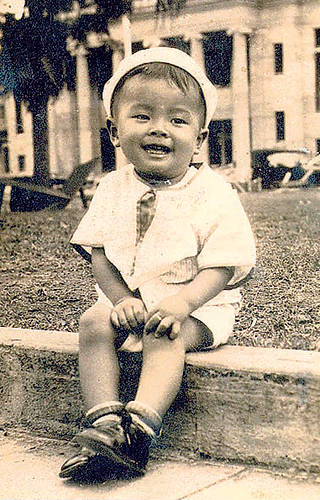

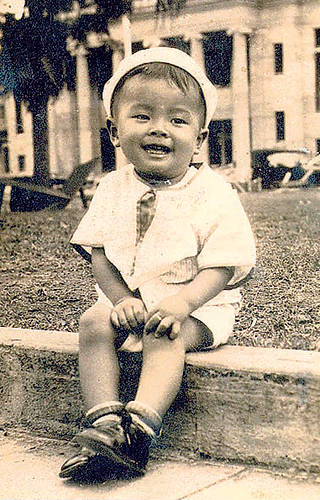

Inouye was born in 1924 to a jewelry-clerk father and homemaker mother. He and his three siblings were raised in a hardworking household that emphasized discipline and family honor.

Inouye was born in 1924 to a jewelry-clerk father and homemaker mother. He and his three siblings were raised in a hardworking household that emphasized discipline and family honor.

« Previous article: A hero for Hawaii (1 of 9)

Born in Honolulu on Sept. 7, 1924, at home on Queen Emma Street with the help of a midwife, Inouye grew up in McCully and Moiliili, which were then largely poor, working-class Japanese-American neighborhoods.

His father, Hyotaro, came to Hawaii as a young boy with his parents, who were lured by recruiters to work in the sugar plantations on Kauai. They had planned to stay only long enough to pay off a $400 debt caused by a fire that had started in the family home in a small village in Yokohama in southern Japan. But they ended up making a new life in the islands over the decades it took to raise the money and send it back home to compensate the other villagers.

|

"All I wanted to do was carry a rifle." |

His mother, Kame, was born on Maui to Japanese parents but orphaned as a young girl. She lived with a Hawaiian family and, later, the Rev. Daniel Klinefelter, who led a Methodist orphanage and had a deep respect for both Hawaiian culture and Christianity.

Inouye’s parents met at church and always preached family honor and discipline, a blend of Japanese tradition and Methodist sensibility. Inouye was the eldest of four children — sister May and brothers John and Robert — and was named for Klinefelter and the biblical prophet Daniel.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

In his 1967 autobiography, "Journey to Washington," written with Lawrence Elliott of Reader’s Digest, Inouye recalled that he did not wear shoes regularly until he reached McKinley High School. His father, a jewelry clerk, and his mother, a homemaker, "were so caught up in the adventure of raising a family, and worked so hard to preserve and protect it, that apparently they had no time to worry about being poor.

"There was always enough to eat in our house — although sometimes barely — but even more important there was a fanatic conviction that opportunity awaited those who had the heart and strength to pursue it."

Inouye learned to speak Japanese at home and attended Japanese school in the afternoons after his public school classes had ended. But he always saw himself as an American first and took the country’s revolutionary history and the democratic ideals of the Founding Fathers as his own. He explained, with some degree of pride, that he was thrown out of Japanese school as a teenager for challenging a jingoistic priest.

His family, he wrote, had "a sort of built-in eagerness to become part of the mainstream of American life."

As a teenager, Inouye liked tropical fish, homing pigeons and big-band giants like Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller. He also liked pool and cockfighting, but said the closest thing he came to real trouble was being caught underage at a pool hall.

Inouye wanted to be a doctor and had taken a first-aid course from the American Red Cross, but he was not emotionally prepared for what he saw after Japanese fighter planes filled the skies over Oahu on Dec. 7, 1941.

The Red Cross called him into service at an aid station at Lunalilo School, where he cared for the civilian victims of the attack on Pearl Harbor, including many who were injured by friendly fire.

The surprise bombing, which he would later describe as a "monstrous betrayal," changed the direction of his life. It also exposed him to the racism that infected the United States, even in a territory as diverse as Hawaii. He felt no matter what Japanese-Americans did to fight Japan and Germany in World War II, or the extent of their sacrifices at home, "there would always be those who would look at us and think — and some would say it out loud — ‘dirty Jap.’"

At the time, nisei were not allowed in the military, so Inouye enrolled in premedical courses at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt agreed in 1943 to let nisei volunteer for the war, Inouye believed the president was speaking to him. "Americanism is a matter for the mind and heart," Roosevelt said. "Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry."

Inouye was initially passed over by the Army because he was already serving the war effort with the Red Cross. But he was so eager, and so driven by instinct to prove his loyalty, that he quit the aid station and was among the last chosen in Hawaii for the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. "All I wanted to do was carry a rifle," he remembered.

His father gave him a simple piece of advice before he left for basic training on the mainland: "Don’t bring dishonor to the family."

Drawn from nisei volunteers from different social backgrounds, the segregated 442nd had to overcome tensions between the "Buddhaheads" — brash young men from Hawaii, where much of the population was Asian or Hawaiian — and the "Katonks" — more reserved young men from the mainland, who were more culturally isolated and lived in places where racism was much more overt. At Camp Shelby in Mississippi, there was bad blood, fistfights and some real doubts about whether the nisei could work together as a combat unit. (The Katonks got their nickname for the sound of being whacked on the head.)

Years later, Inouye told an interviewer for the 1992 book "Boyhood to War," a collection of anecdotes about the 442nd by Dorothy Matsuo, that the mood changed when the soldiers visited a Japanese internment camp in Arkansas. The Buddhaheads realized that some Katonks had volunteered even though their friends and families were locked behind barbed wire. "The Hawaiian asked himself that day, ‘Would I have volunteered?’" Inouye said. "I would like to say, ‘Yes.’ But not having faced it, I can’t say what I would have done."