Educational assistant has reassured kids since 1966

LEE CATALUNA / LCATALUNA@STARADVERTISER.COM

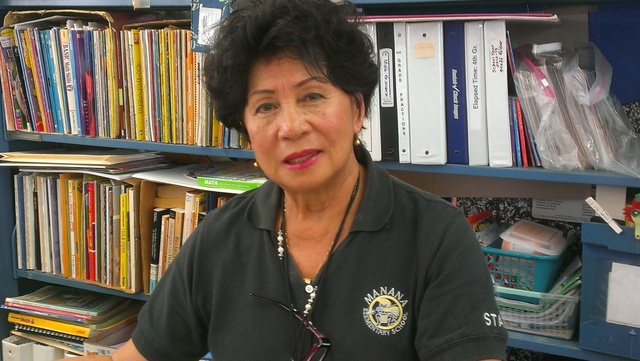

Liz Agbayani has been helping small students with big problems for 50 years as an educational assistant for the state Department of Education.

I’m early for my appointment to meet one of the longest-serving employees of the Hawaii Department of Education. The change in timing doesn’t bother her. Not much does.

“It’s OK,” is her motto.

Liz Agbayani comes to greet me. In a trim white skirt, wedge heels and fuchsia lipstick, she does not look 76 years old. I decide not to ask when she plans to retire.

Agbayani (no relation to Benny) has worked as an educational assistant for the Hawaii Department of Education since 1966, the last 32 years at Manana Elementary. She works one-on-one with special education students, but she’ll help any kid who asks, no matter what they ask.

Agbayani was a 26-year-old mother of four when she heard that schools were hiring classroom assistants. “I applied because I wanted to save for a home for my children,” she said. “As it turned out, I loved the job.”

It required quickly figuring out what a child needs and coming up with creative ways to approach learning. Agbayani usually begins with, “It’s OK,” because if you start there, you have reason for hope and the heart to work for better.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

For 14 years, she worked at Washington Intermediate in different roles, but her favorite was as educational assistant for “special motivation” — a term for kids who are capable but for some reason are not engaged in school. “I loved working with those students. I really did.”

One of her favorite stories was of a girl who, at first, wouldn’t speak to her. For weeks, the girl would sit on the steps outside Agbayani’s class, silent and sullen.

“Slowly, she started to open up to me. She told me she was the only one in her family who handled the bills. She told me, ‘My stepfather sells all my things. I hate my mom for letting him sell my things.’”

Agbayani tried to be positive. “I told her, ‘I commend you for all you do. Someday, it will turn OK.’”

Agbayani ran the school’s May Day program, and that year, she decided to put all her special motivation students on the May Day Court.

The student who had sat on the stairs for two weeks without talking would be the queen.

“She told me, ‘You know I walk like a man, right?’ I said, ‘That’s OK.’ And every day after school, we had 10 minutes of walking lessons with a book on her head.”

The May Day program got rained out, so the event had to be squeezed into the school cafeteria and performed twice so the entire school could see. The girl’s parents stayed to see both shows.

“She told me afterward, ‘My mom said nothing wonderful like this ever happened in our family,’ ” Agbayani said.

All her stories start with a challenge and a kid who was full of potential.

She was asked by the school if she could work with a 5-year-old in kindergarten who was blind. “They told me to go and just observe him in the classroom.”

She did. The boy just sat quietly with his chin almost to his chest. He didn’t interact with anyone or react to the noises around him. He wasn’t intellectually impaired; he just didn’t know what was going on.

“I went to a team meeting for this boy and we were told, ‘Dream big for this kid’,” Agbayani said. “I thought, OK, I’m gonna dream big for this kid. I’m going to teach him what this world is about.”

Her idea was to give him images in his mind of things he could never see.

Agbayani told the kindergarten teacher that she was going to come to the class and take the boy for a walk. “We’re going to touch things. Metal, wood, plastic, cement, everything,” she told the child.

As they were walking, the wind rustled the leaves of a tree. “‘What’s that?’ he asked me. I said, ‘That’s a tree.’ I had to go get him the leaves so he could touch the leaves. Then he heard children playing. ‘What’s that?’ he asks. ‘That’s your classmates. They’re running around for recess and they’re screaming,’ I said. ‘What’s screaming?’ he asked.”

Agbayani shakes her head . “Oh, my heart broke when he asked that. I said, ‘OK, I’m going to teach you how to scream.’”

Agbayani took the boy to the playground, got on a swing and put him on her lap. As they swung together, she talked to him. “You feel the wind on your face? It’s exciting, right? OK. We’re going to scream together. Ready?”

And they did.

The boy had more questions. What is the wind? What is the sun? What is an earthworm?

For that last one, Agbayani asked a school custodian to help her find an earthworm. The custodian knew just where to dig. He brought the earthworm to Agbayani and she placed it carefully in the boy’s hand.

“He said, ‘Oh, it’s moving!’ I told him, ‘Yes, and he lives in the dirt and we’re going to put him back now.’”

Afterward, another teacher passed them and said hello to the boy. He excitedly told her what he had just done. “You know what? We touched an earthworm and it moves like this.” And he moved his hands like a worm. Agbayani was floored. The boy had made a huge connection. He could describe something he couldn’t see.

That boy is in college now.

After 50 years of telling kids it’s OK and helping them make it so, she has stories that could fill a bookshelf.

Agbayani has eight grandchildren and 10 great-grandchildren. Her oldest daughter teaches high school in California. “She’s thinking of retiring. She might retire before me!” Agbayani says.

Since she brought it up, I decide to ask.

“I’m thinking maybe I’ll retire in the next two years,” she says.

“But what will you do with all your energy?” I ask.

“Exactly!” she says. “I might as well keep working.”

7 responses to “Educational assistant has reassured kids since 1966”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Wonderful story about wonderful woman.

There are some that just need a little kindness. Evidently she has found a niche where can be helpful and enjoy helping others help themselves. A gift she has which many of us do not possess. She has been blessed by bringing joy to others. You’ve gotta love this story of a remarkable person, alo most saintly.

Everyone was nice and committed to excellence back in the 1960s. Now they are a one in a million.

1966 in Hawaii was before we started to waste tax money on the rail, homelessness, and the teacher’s union.

Keep up the great work Mrs. Agbayani! The world needs more people like you.

Ige could begin to paying attention our resolute residents of Hawaii for going beyond the call of duty.

What a great story and women!