Discharged hospital patients find care, shelter at Tutu Bert’s House

BRUCE ASATO / BASATO@STARADVERTISER.COM

Teresa Lyon Nielsen described her injuries and medical treatment as she sat in her wheelchair outside Tutu Bert’s House last week in Kalihi.

BRUCE ASATO / BASATO@STARADVERTISER.COM

Staffer Eleanor Vaimanino puts food away in the renovated first-floorkitchen.

BRUCE ASATO / BASATO@STARADVERTISER.COM

Scott Lenahan is recovering at Tutu Bert’s House after he was injured in a motorcycle crash in Kailua-Kona.

BRUCE ASATO / BASATO@STARADVERTISER.COM

Terry Lauro sits in her wheelchair in the renovated living room at Tutu Bert’s House. Lauro, 54, was discharged from Queen’s Medical Center two weeks ago after surgery for a painful bacteria-borne skin infection. “I’m getting stronger now,” she said.

The Institute for Human Services and the Queen’s Medical Center today will bless a new home in Kalihi for medically frail homeless people.

Patients such as Teresa Lyon Nielsen call the service a lifesaver.

On March 3, IHS opened Tutu Bert’s House — named after the 93-year-old widow of IHS’ founder, Father Claude DuTeil — to the first of what it hopes will be 60 homeless patients annually like Nielsen who would otherwise be vulnerable to assaults and thefts as they try to heal on the street.

>> What: Two-story, three-bath, 3,816-square-foot, seven-bedroom residential home in Kalihi for “medically frail” homeless patients discharged from the Queen’s Medical Center

>> Length of stay: 6 weeks

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

>> Services: Medical treatment, social service help finding a home

>> Cost savings: $2.68 million annually on Medicaid costs not used at Queen’s

Source: Institute for Human Services

Nielsen, 62, a longtime fixture at the homeless encampment at Atkinson Drive and Ala Moana Boulevard across from Ala Moana Center, recently spent 20 days at Queen’s for a strep infection in her right toe that required surgery while also recovering from a torn retina, which she sustained after being punched in the right eye by another homeless person.

Last week, she sat in a wheelchair outside Tutu Bert’s House. Wearing a black patch over her injured eye, Nielsen said she could not imagine successfully following her doctor’s orders to “rest and keep her (injuries) clean” had she returned to an encampment.

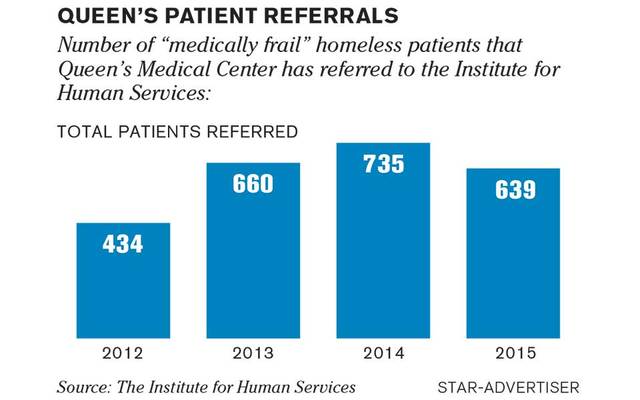

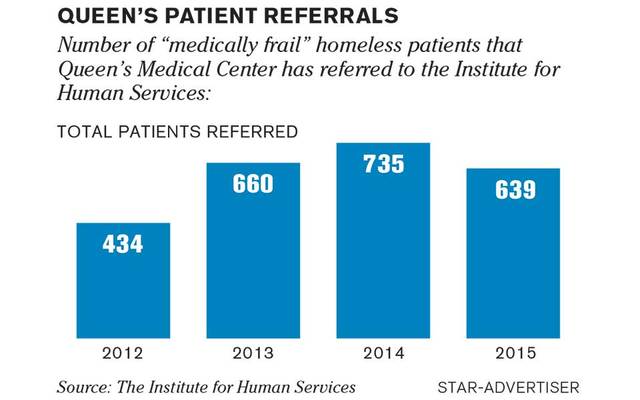

Last year, Queen’s referred 639 homeless patients like Nielsen to IHS’ shelters, where it’s difficult for them to get the proper follow-up medical treatment they require after being discharged from the hospital.

In many cases, patients with no place to go — and who are too frail to take care of themselves — end up using valuable hospital space at Queen’s, said Loraine Fleming, Queen’s director of behavioral health, medicine, transplant and geriatrics.

So Queen’s approached IHS Executive Director Connie Mitchell to brainstorm alternatives, and Mitchell came up with the idea for a new home to provide up to six weeks of care and shelter for as many as eight patients at a time, receiving not only medical treatment but also social service help for their issues and assistance finding a permanent home.

Tutu Bert’s House serves “a group of patients who no longer need intensive hospital care but still require some level of oversight and supervision, more than they would be served in a shelter setting,” Fleming said. “Connie put forward the idea of an exclusive house for Queen’s patients that they would manage. It sounded like a wonderful idea. It’s a total waste to have them stay in a hospital bed, but we don’t want them to return to their homeless situation, where they might not get follow-up treatment.”

IHS estimates that the eight beds in Tutu Bert’s House conservatively will save taxpayers $2.68 million every year in Medicaid costs that would have been used to treat homeless patients at Queen’s.

“Many require a high level of medical care and it’s really difficult to care for these patients at the shelter,” Mitchell said. “And a shelter is not a good place for people to recover, especially if they require intravenous antibiotics. We have a real need for this type of housing.”

Many of the patients staying at Tutu Bert’s House last week relied on wheelchairs. But patients must be ambulatory enough to use the toilet or take a shower on their own.

IHS rents the two-story, three-bath, 3,816-square-foot home at a cost of $4,200 per month. Patients double up in seven bedrooms, with enough extra space to ensure that patients are paired according to gender.

The house was in such poor shape that walls were torn out and new appliances, fixtures and other materials were brought in, including renovations to make the home compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Alexander & Baldwin, Castle & Cooke and Stanford Carr Development donated the equivalent of $150,000 worth of materials and labor.

Nani Medeiros, executive director of the new nonprofit group of Hawaii builders and developers called HomeAid Hawaii, said in a statement: “The building industry’s response and willingness to address homelessness not only saves IHS money from labor and hard costs to renovate the home, but it allows the nonprofits to dedicate their limited resources to provide program services, which is needed the most.”

Terry Lauro, 54, was discharged from Queen’s two weeks ago after surgery for a painful bacteria-borne skin infection from both ankles to her knees called cellulitis, which can lead to blood clots.

It took three Queen’s surgeons seven hours to “clean me up,” Lauro said.

Lauro requires antibiotic IV injections three times a day to prevent infection and blood clots and said it would be nearly impossible to keep her legs clean on the street.

She spent seven years, off and on, homeless from Waikiki to Honolulu Airport sleeping in “parks, beaches, benches.”

At Tutu Bert’s House, Lauro said from her wheelchair, “I’m getting stronger now.”

Scott Lenahan, 32, moved from New York to Kailua-Kona seven months ago with no place to live and no job.

He finally found work in construction and had just spent his first month in a $1,000-a-month, one-bedroom apartment when he crashed his friend’s 2006 Yamaha R1 sport motorcycle while riding back home from Ocean View.

He spent two weeks on life support in Kona and ended up in Queen’s with no spleen, 12 broken bones, a right leg that had been “filleted open with my bone showing,” a double fracture in his right arm, 30 staples in his left leg and a total of 109 staples in all.

Lenahan was not wearing a helmet and miraculously suffered no head injuries.

“But my right hand might never work again,” he said. “It’s got permanent damage.”

By the time he was able to stand with the help of a cane, Lenahan learned that he had been evicted because he had been unable to contact his landlord, who disposed of everything Lenahan owned, including all his clothes and a television.

“I have one pair of pants and two or three shirts — all donated,” he said.

With no place to live, no job and injuries on most of his body, Lenahan has no idea what the future holds.

But at least he’ll have six weeks to recover at Tutu Bert’s House, where he’ll get help figuring out his next move.

“I’m so happy here,” Lenahan said. “If it wasn’t for this place, I don’t know what I would have done.”

12 responses to “Discharged hospital patients find care, shelter at Tutu Bert’s House”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Wonderful news — and a great collaboration between Queens and IHS.

It’s nice that Queen’s gets recognized for doing this. In this state our government has shunned its responsibilities for the homeless dumping it on institutions like IHS and Queens.

Are you kidding me? Who do you think funds IHS? Go look at their annual report and see just how much government money IHS takes in. I’m not saying its bad, I would much rather have IHS providing services that a government agency. BTW the reason Queen’s is supporting this is because it benefits Queen’s. Under the affordable care act they get penalized if a patient is re-admitted to the hospital within 30 days of their discharge. Medical half way houses are a lower cost option for continued care to prevent a costly hospital re-admission.

Yes, it won’t be Queens discharging patients on the streets, it will be Tutu Berts. Merely for PR purposes it protects Queens good name and likewise still cost the taxpayers. A ruse to put the onus back on the taxpayers.

You don’t seem to understand. The fact that it benefits Queens disguises the fact that these patients often get sent to Queens because no one else wanted them and the State doesn’t have a safety net hospital on Oahu. There’s no way that the State’s support of IHS comes even close to the cost of a hospital. In addition, if you looked closely, what you’re going to find is that most of the other hospitals take very few of the patients that Queens gets dumped with.

IHS rents the house for $4200/month, $150K was contributed for renovations and repairs? Who’s the lucky landlord?

What a wonderful organization! God bless them for what they are doing. God’s work.

From New York to Hawaii with no money or job lined up. No plans before moving here? Great he gets a job but goes on a motorcycle and gets into an accident…..

I would imagine there are people from Hawaii who move to the mainland with no job and no place to live as well. At least the dude went out and found a job which means he is probably not a deadbeat guy who came here to leach social services from our State.

good point

This is a good addition to the array of services for houseless individuals. Great interventions can be designed when there is a willingness for organizations in the community to put their heads together creatively to work on a mutually valued outcome. Bravo.

Couldn’t Hawaii lawmakers greatly expand on this already successful “Tutu Bert’s House” collaborative program in order to help a greater number of homeless individuals & families? And hopefully for a longer stay than a short 6 weeks? – if the person/family needs more time to heal, transition into more permanent housing, &/or get their lives back on track. This home environment (living in an actual HOUSE w/small yard, appliances, etc.) is more humane, nurturing, uplifting, healing; than having to live en masse in a large box (“renovated” former Matson container) or in a flimsy tent…

Wow, that former landlord of Scott Lenahan is COLD. Hope HE gets what he deserves someday! Some people have no heart.