Charter school stands accused of nepotism

Principal Diana Oshiro of Myron B. Thompson Academy Public Charter School says she values "blind loyalty" and has hired several relatives — including her sister and three nephews — because she can count on them to do what she says.

Three out of four administrators at Thompson, one of the state’s largest charter schools, are part of Oshiro’s family. Her sister oversees the elementary school as vice principal and also works as a flight attendant.

Oshiro’s nephew is the athletic director, although the school had no sports teams last year or this year, and he doesn’t teach PE. He and his brother, the film teacher, were hired with just high school degrees, although public school teachers are supposed to have bachelor’s degrees and teaching licenses.

A veteran educator, Oshiro was blunt when asked about her hiring practices at the online school, which has 517 students in kindergarten through 12th grade.

"I pick certain people with certain characteristics and blind loyalty — that’s uncomfortable to say, but I believe it," she said. "The people who are closely connected to you, you don’t have to worry about whether you can trust them and what they’re likely to do. If people want to challenge that, be my guest. It’s about deliverables and outcomes."

Others say that nepotism at the school shortchanges students as well as taxpayers who pay the salaries of unqualified or unproductive family members. The case raises questions about accountability at charter schools, which have great freedom in choosing their staff and running their campuses although they are publicly funded.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

"There are extreme cases of nepotism and favoritism," said Olu Bicoy, a former teacher at Thompson Academy who chose to leave several years ago. "As teachers, we had to go through the Hawaii teacher certification process. However, the family members that were also teaching didn’t even have college degrees.

"If your son, daughter, niece, nephew or grandkid is the most qualified person for the job and there is no one else on the planet who can do the job better than him, great," she said. "If they aren’t, it is your obligation to look elsewhere first."

Justin Nidgion, who taught for five years at Thompson Academy before becoming fed up and quitting earlier this year, said: "I was surprised to find that a family can own a public school, and it’s not the family whose name is on the school. In their deeds and actions, they treat it like they own it."

Charter schools are autonomous public schools overseen by their own boards. They are exempt from most state regulations. They receive funding from the state on a per-pupil basis and are supposed to be accountable for educational results and fiscal management.

Malia Chow, chairwoman of Thompson’s school board, said board members only recently became aware of concerns over nepotism and are addressing the situation. The 11-member board is drafting a policy on hiring and reviewing applicants who are relatives, "so that family members are not involved in the hiring and review," she said.

"The school board really does put the students first," Chow said. "These sorts of accusations we will take seriously and look into. The school board has not been involved in hiring practices. The issues you’re raising will cause us to look more closely into it.

"We didn’t know about this and only wish we had known about it sooner," she added.

FOUNDED IN 2001 and headquartered in a squat, black-glass office building in Kakaako, Thompson is a "virtual school" whose students work from home via computer rather than going to campus daily. Students communicate with their teachers largely via the Internet, and come to campus for electives, such as performing arts. In the elementary school, parents say it resembles homeschooling, except they receive guidance from Thompson teachers and a $1,500 annual allotment to pay for curriculum, supplies and outside activities such as judo or ballet.

In 2002, school administrators asked the family of Myron B. Thompson, former trustee of Kamehameha Schools and president of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, whether they could name the school after him, and reserved a seat for a family member on its school board.

Eldest son Myron K. Thompson, who holds that seat, said the question of nepotism came up during a recent audit as well as in inquiries from the Star-Advertiser. He said the board is taking steps to deal with it, but added that "if the people are performing properly, that’s probably the most important issue."

"I’m really proud of the school and proud of what Diana and her staff have done," Thompson said of Principal Oshiro. "From a reputational point of view, we will do anything that we need to maintain the integrity of the school. We will address it professionally and do the right thing, and get it squared away."

Without a traditional campus, Thompson Academy remains largely out of sight. Its teachers are reluctant to complain ; all are on year-to-year contracts, despite a provision in the teachers union contract that they should be eligible for tenure after three years. After receiving anonymous complaints, the Star-Advertiser tracked down eight former staff members, most of them teaching at other public and private schools. All of them said family members at Thompson could ignore the rules, and came and went as they pleased.

» Oshiro’s sister, Kurumi Kaapana-Aki, is vice principal of the elementary school but also works full time as a flight attendant for Hawaiian Airlines, according to co-workers at the school and the airline. Although Thompson teachers are expected to attend school daily, she was often absent, the former staff members said. Kaapana-Aki did not return phone calls from the Star-Advertiser.

"She was not even showing up at work but she’s still collecting money from the state to be a vice principal," said Brayden "Kaleo" Ramos, a former Thompson faculty member who now teaches at Halau Ku Mana charter school.

» Kaapana-Aki’s son, Andrew Aki, is the athletic director, although the school has not had a sports team for two years and he does not teach the online PE course. Asked what he is doing for students at Thompson, Oshiro said he is organizing activities such as Jump Rope for Heart. Aki was hired more than six years ago with just a high school degree. He is enrolled in the first year of two-year associate’s program at Leeward Community College that trains teacher assistants, according to the college.

» Zuri Aki, Andrew’s brother, was hired in 2003 also with a high school degree, and teaches film. In May, he earned his two-year associate’s degree in liberal arts at Leeward Community College. Nidgion said Aki’s classes at Thompson largely consisted of watching movies and playing video games with students. "The sad thing about it, he wouldn’t show up in time to open the door for the class," Nidgion said. "They would be in the hall for an hour waiting for him, causing trouble."

Zuri and Andrew Aki also declined to be interviewed.

» A third brother, Hanan Aki, works part time as a clerk at Thompson.

The school did not respond to requests for specific salary information, but a 2008 payroll document obtained by the Star-Advertiser showed that Zuri and Andrew were making $28,800 a year for their part-time jobs, while their brother, Hanan, was earning $22,100. That is relatively high, considering that Hawaii public school teachers who do have bachelor’s degrees but have not yet completed a state-approved teacher education program start with a salary of $32,700 for full-time work.

The pay for Oshiro and Kaapana-Aki wasn’t listed on the document. Under the union contract for regular public schools, principals earn from $72,500 to $162,400, and vice principals make from $58,400 to $130,900 annually, depending on experience.

Thompson lists 37 teachers, four counselors, four administrators and 16 support and clerical staff members on its website. Asked whether having five members of the family on the payroll constitutes nepotism, Oshiro said she often hears that term.

"I don’t know how to explain it except that’s the way it is," Oshiro said. "If people have concerns, they should come and see me. Because I do believe that some of what we’re doing here works because of all the connections, that includes all the teachers."

IN CONTRAST to the criticism from former teachers, some long-term faculty at Thompson strongly support Oshiro and say they appreciate the atmosphere of "ohana" at the school. They describe the online school as a "24-7" environment that requires flexibility and willingness to try new things.

"It’s an interesting dynamic in that with family, you can rely on them, you can ask more of them, you can work longer hours if needed," said Jacey Waterhouse, an English teacher who has been at Thompson for eight years. "A lot of us are like a family. We’ve been through the ups and downs. We push innovation and try to look at things outside of the box and tailor things to the students’ needs."

Jerelyn Watanabe, a math and science teacher who also works in the registrar’s department, described the school as "a wonderful place to be."

"Diana is a visionary leader," Watanabe said. "We try anything that is going to benefit our students. The people that work here get their jobs done. It’s a very, very productive place."

Cydney Shabazz, who teaches kindergarten, said Kaapana-Aki has been coming to school daily, and "I’ve loved having Kurumi as my boss. She’s accessible, easy to talk to."

Before becoming Thompson’s principal, Oshiro was an assistant superintendent of the Department of Education and helped develop the "e-school" concept.

Elizabeth Blake, vice principal at Thompson during 2001-05, said she recruited Oshiro to head the school and that she was "a great principal" until she started hiring her relatives.

"Then it got really, really bad," Blake said. "Not only did she hire the nephews, she hired their girlfriends. That’s what happens when you have a charter school that has money from the state that can run autonomously.

"I believe in the charter school movement," Blake added. "There has to be some finite law put in place about hiring procedures, all that stuff."

Blake said she challenged Oshiro over the performance of her relatives and was later fired. She said she tried unsuccessfully to get a hearing with Thompson’s school board.

"They only get told what Diana wants them to hear," Blake said.

Charter schools are supposed to post the minutes of their board meetings publicly, but Thompson had not done so for a year until the Star-Advertiser notified the school board. On Tuesday, the minutes of two meetings conducted by phone in October and November were added to the school’s website. Oshiro takes minutes for the board, usually just a few paragraphs.

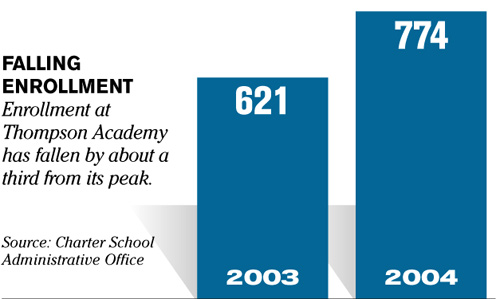

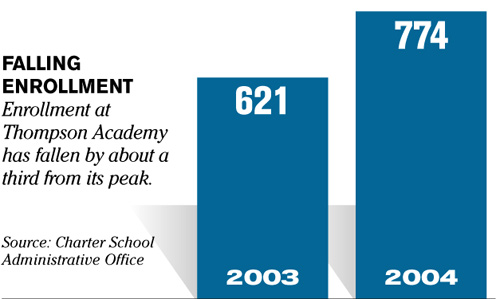

Thompson’s enrollment has been shrinking since its peak of 774 students in 2004. It has 517 students this year. Meanwhile, Hawaii Technology Academy, a second online charter school that opened in 2008 with 237 students, has mushroomed to 1,000 students enrolled as of October. Director Jeff Piontek said the school does not recruit from Thompson, but receives many applications from its students and teachers. So far, 118 students have shifted to his school from Thompson.

Thompson’s reading scores are high, but the school has been in "restructuring," the strongest sanction under No Child Left Behind, for missing academic and other benchmarks. On the latest Hawaii State Assessment, 86 percent of Thompson students were proficient in reading and 49 percent proficient in math, meeting state targets, but the school is still in restructuring because its graduation rate fell short.

"This is the first year that we made it across all academic benchmarks, so I’m really happy about that," Oshiro said.

Along with Oshiro’s family, Thompson Academy also has several members of another family on staff. Dee Yamane is the vice principal for the secondary school; her daughter handles data management; her daughter-in-law is the health teacher; and her husband gets paid for custodial work.

While some observers say family members get a pass and can ignore the rules at Thompson, Oshiro contends they are subject to tougher scrutiny.

"In many cases when you do have family members on board, we’re pretty much harder on them," Oshiro said. "I know I have to be extra harsh on folks that are closer to me, whether they are friends or family. The one thing that I can count on for Dee as well as Kurumi, I know they are going to follow through with my directives. I can trust whatever my directives are, they will be implemented."