Asian-American jab at Oscars reveals deeper diversity woes

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Host Chris Rock’s skit ignited an outcry from Asian-Americans and others angered by its stereotyping and, more broadly, frustrated by how non-black minorities are portrayed - or ignored - by Hollywood, especially movie studios. The response also has illuminated the gap between African-Americans, who have made on-screen gains, and the lagging progress by other minorities including Asian-American, Latinos and Native Americans.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Constance Wu, who found success on TV starring in ABC’s immigrant family drama “Fresh Off the Boat,” doesn’t see deliberate discrimination in Hollywood. “The biggest roadblock I’ve found is not people with bad intentions,” Wu said. It’s a lack of imagination about the type of roles that Asian-Americans can play. They want to include them but they don’t know how, unless as a stereotype supporting a white man’s story” or an Asian foreigner.

ASSOCIATED PRESS

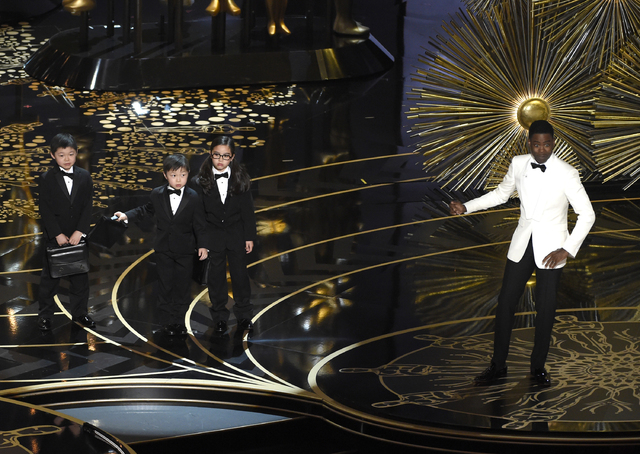

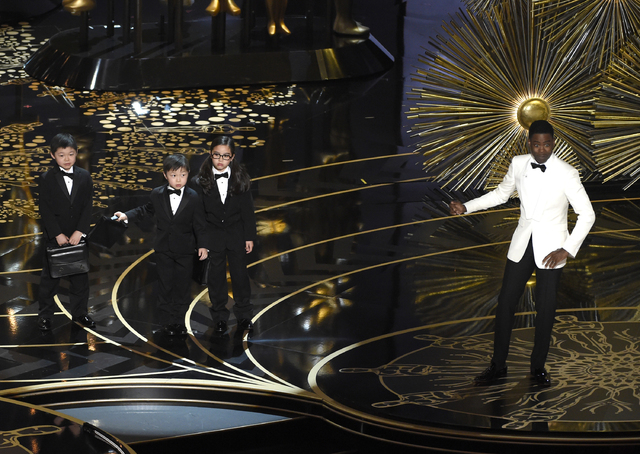

Nahnatchka Khan, “Fresh Off the Boat” creator, was reveling in Oscar host Chris Rock’s deft comedic assault on white-fixated Hollywood at the 88th annual Academy Awards on Feb. 28, 2016. Then three Asian-American kids were brought onstage for a gag mocking them as ethnic stereotypes. “It was completely shocking and just so unnecessary,” said Khan.

LOS ANGELES >> TV’s “Fresh Off the Boat” creator Nahnatchka Khan was reveling in Oscar host Chris Rock’s deft comedic assault on white-fixated Hollywood. Then three Asian-American kids were brought onstage for a gag mocking them as ethnic stereotypes.

“It’s like going on a road trip with your fun friend, and halfway to Vegas he pulls over and shoots you in the leg,” Khan said, recalling her reaction to last weekend’s ceremony. “It was completely shocking and just so unnecessary.”

Rock’s skit ignited an outcry from Asian-Americans and others angered by its stereotyping and, more broadly, frustrated by how non-black minorities are portrayed — or ignored — by Hollywood, especially movie studios.

The response also has illuminated the gap between African-Americans, who have made some on-screen gains, and the lagging progress by other minorities, including Asian-American, Latinos and Native Americans.

Phil Yu, who observes Hollywood as part of his Angry Asian Man blog, said he welcomed the #OscarsSoWhite protest against this year’s all-white slate of acting nominees. But, as in years past, Yu said he was struck anew by the greater challenge Asian-Americans face.

“When I watch the Oscars as an Asian-American, I think, ‘It must be kind of nice to be disappointed that there were roles to be overlooked.’ I wonder what that feeling is like, because I can name no Asian-Americans that were in contention,” he said.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

That perception is borne out by a comprehensive study released last month by the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

At least half of all movie, TV or streamed projects from September 2014 to August 2015 lacked even one speaking or named Asian or Asian-American character, the study found. By comparison, 22 percent didn’t include any such roles for black characters. Of lead characters that were minorities in 100-plus movies, nearly 66 percent were black and 6.3 percent were Asian.

In the U.S. population, African-Americans are a greater percentage, 12.3 percent, to about 5 percent for Asians.

But Rock’s attack on the industry’s diversity failures was fully black-centric, from one-liners to Black History Month skits. Then came the tuxedoed Asian-American kids, whom Rock presented as the “dedicated, accurate” accounting team that tallied Oscar votes, adding, “If anybody’s upset about that joke, just tweet about it on your phone, which was also made by these kids.”

Basketball player Jeremy Lin did just that. “Seriously though, when is this going to change?!? Tired of it being “cool” and “ok” to bash Asians,” he posted on his Twitter account.

Rock declined a follow-up interview through his publicist. And the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, as well as the ceremony’s producers, did not respond to requests for comment.

Rock had company at the Oscars. Presenter Sacha Baron Cohen, in character as Ali G, made a sexually demeaning crack about “little yellow people.” Despite his pretense of talking about Minions, the cartoon characters, it was considered a slap at Asians.

Such humor, especially from the host, made the evening’s “relentlessly black and white” take on diversity even more disheartening, said Daniel Mayeda, co-chair of the Asian Pacific American Media Coalition. To an extent, that dual focus parallels the movie industry itself.

“There have been significant changes in television. Film is way behind,” said Mayeda, whose group is part of an umbrella organization, the Multi-Ethnic Media Coalition, that’s prodded the TV industry since 2000 to boost minority hiring and last month announced it was targeting movie studios to do likewise.

He and other coalition leaders have said the quest for opportunity should not pit minorities against one another and that Hollywood must make room for all groups.

But there are specific biases and challenges to overcome, said Nancy Wang Yuen, a Biola University sociology professor who conducted a wide range of interviews for her forthcoming book, “Reel Inequality: Hollywood Actors and Racism.”

“One casting director told me the industry perceives Asian-American actors as inexpressive,” Yuen said. “If this is the kind of stereotyping against Asian-Americans as a race, then that really disadvantages them from being cast.”

Hollywood has a dismal track record in depicting Asians and Asian-Americans that goes beyond invisibility. Actors have suffered the further indignity of losing major roles to white actors, including Luise Rainier as a Chinese peasant in 1937’s “The Good Earth” and Marlon Brando as a Japanese interpreter in 1956’s “The Teahouse of the August Moon.” Rainier won an Oscar.

And the practice hasn’t stopped. In last year’s “Aloha,” Emma Stone played the half-Asian character Allison Ng, a casting decision that drew howls of protest.

Constance Wu, who achieved success starring in “Fresh Off the Boat,” an ABC immigrant family drama, doesn’t see deliberate discrimination.

“The biggest roadblock I’ve found is not people with bad intentions,” Wu said. “It’s a lack of imagination about the type of roles that Asian-Americans can play. They want to include them but they don’t know how, unless as a stereotype supporting a white man’s story” or an Asian foreigner.

Jason Lew, whose “The Free People” premiered this year at the Sundance Film Festival, also called on the industry to expand its vision.

“A lot of the stories I want to tell are about my people — the Asian-American experience. And I constantly run into, ‘Well, who’s going to be in it?” It’s a catch-22,” Lew said. “Who’s going to be in it is my amazing Asian-American cast who are going to have big careers and make money for you guys, but you have to give them a chance. You have to start somewhere. “

22 responses to “Asian-American jab at Oscars reveals deeper diversity woes”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I was wondering when someone would finally bring this up. The blacks are always complaining. What about Asian Americans??? Why can’t it just be about who is the best Actor??? Did Leonardo complain when he lost to another actor, who happened to be black???

Good point!!!! Did Reagan complain about the mess he inherited from Jimmie Carter??????

Has been going on for decades. From Mickey Rooney as Mr. Yunioshi in “Breakfast at Tiffany’s” to David Carradine as Kwai Chang Caine in “Kung Fu”. The problem is while where society has embraced racial acceptance Hollywood is still slow to come around.

Goes way back to the Los Angeles riots and lynching of Asians:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_massacre_of_1871

Consider the source -Chris Rock, is a comedian.

He’s on stage with a captive audience.

He makes jokes for a living.

The more ‘controversial’ or ‘sensationalism’ he causes makes headlines.

Nahnatchka Khan & Jeremy Lin have become too over-reactive to this phenomenon and must understand

the ‘source’.

I remember seeing an Asian pictured in the computer/diagnostics portion of a

Sears ad. Is that racist?

I didn’t watch the Oscars, but Chris Rock’s opening monologue on You Tube was hilarious!

I didn’t see this asian gig on You Tube, though. Just from what I read and the photo, it looks really cute! What’s to complain about (don’t answer that!). I just think it looks cute, and that’s coming from the water of mixed kids.

What’s the big deal? Just look at the Asians here in Hawaii, especially the richer Chinese and their kids. They ALL act like whites and live like whites with no pride in their Asian heritage. Just watch the rich Asians who send their kids to Punahou or Iolani. There’s not a hint of Asian pride in any of them and their kids think they’re white

By the way, I’m not knocking the schools as my kids went there (although diversity education is lacking).

Maybe it’s because they’re better equipped academically to be accepted into these private schools. Isn’t that a criteria for most private schools?

That my friend starts, and ends, at home.

“act like whites”, “live like whites”, both are ignorant, racist comments. How do “whites” act/live? I’ll answer that for you. There is no such thing as a “white” mode of acting/living. Skin doesn’t matter. There is a wide variety of national origins, standards, morals, political/religious beliefs among the caucasian population. Using the term “white” to lump them all into a single indistinguishable stereotype is offensive, ignorant, and racist.

Yep, aaaverybaaaadddy hates Chris….

the kids parents didn’t have to sign the permission document to let the

kids appear on stage. probably all the parents saw was $$$

You want to find real discrimination against asians? Take a look at the discussion of quotas in the Ivy league universities and the University of California. Disgusting.

I recall Berkeley U. limiting the amount of Asian students because they outnumbered the student population.

Asian students would check the ‘white’ box in fear of getting denied admission because they were Asian.

Blacks/Hispanics were looked upon as not meeting the strict education requirements and listed at the ‘quota’ while meeting a university quota of certain ethnicities.

Yes, the exclusive universities have claimed that Asian-american applicants may have better grades,test scores and extracurricular stuff, but they lack the intangibles…

To better understand the roots of anti-asian racism in the USA, read:

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yellow_Peril

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takuji_Yamashita

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ozawa_v._United_States

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chinese_Exclusion_Act

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Immigration_Act_of_1917

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_v._Bhagat_Singh_Thind

Yes, institutionally lumped into one group no matter what their origins.

“…Nahnatchka Khan was reveling in Oscar host Chris Rock’s deft comedic assault on white-fixated Hollywood.Then three Asian-American kids were brought onstage for a gag mocking them as ethnic stereotypes. ” “It was completely shocking and just so unnecessary.”

So racist jokes and smack downs were funny until it involved Asians? #hypocrite.

Easy solution, just get rid of the Oscar’s. Other wise, if you want to win an Oscar then become a better actor/actress. Quit complaining about the color of your skin.

People need to get a life. Besides Asian’s are way ahead in the technology area. Who needs movies.

The true false impressions are played on Hawaii 5-0. especially having an African American starring as the Governor of Hawaii and another as a law enforcement officer. When has Hawaii ever have an African American governor or an African American as a leading police officer? The producer missed the key point and opportunity to try and portray the real Hawaii by not giving the Asian Americans or locals, the roles of those characters and keep the life style, culture and tradition as close to how the actual lifestyle is in Hawaii. Poor choice of personnel for the positions played by the governor and police officer. This is Hawaii not California or New York.

It’s the makeup of the American Population: majority White, second Hispanic, third Black, fourth Asian. So goes the Oscars, which was founded over 75 years ago, when there were not any at all of Hispanic performers except Cesar Romero, not much Blacks except Sidney Portier, who won an Oscar in the 1960s, and no Asians, except George Takei in Star Trek in 1966. There certainly was Jack Lord though, the original Felix Leiter in Ian Fleming’s “Doctor No” in 1962, and of course our own Steven “Book ’em” McGarrett. I almost forgot about Nancy Kwan in the 1959 feature “The World of Suzie Wong”. Then we have Bill Cosby, Flip Wilson, Sherman Helmsley and more. So there has been diversity. It’s just that Charlton Heston starred in Ben Hur and The Ten Commandments, not George Takei or Bill Cosby or even Don Adams. Oh, Live Long and Prosper, which had Nichelle Nichols, George Takei and William Koenig along with William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy on the Starship Enterprise. Now we have the late Steve Jobs and the Family Fued Host Steve Harvey. Perhaps in a thousand years, we will have returned to The Planet of The Apes to find out that we destroyed ourselves with H-Bombs that made Obama No Care mad and made him push THE button, to initiate The War of The Worlds, which to this is the penultimate Science Fiction film, notwithstanding Star Wars and The Incredible Hulk. This is me signing out, is that u ???!!!