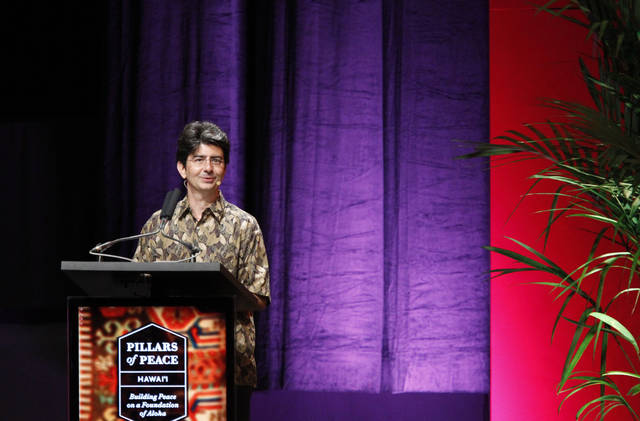

EBay’s founder wants to build dairy on Kauai

STAR-ADVERTISER / 2012

Pierre Omidyar, the founder of eBay, wants to build a dairy farm on Kauai. The goal of Omidyar’s farm is to decrease the state’s heavy reliance on imported milk.

If Pierre Omidyar gets his way, 699 dairy cows will soon enjoy a glorious view of the Pacific Ocean, framed by a pristine beach.

Omidyar, the founder of eBay, wants to build a dairy farm on Kauai.

He is one of many tech billionaires who have established a presence in Hawaii, which is only a five-hour flight from Silicon Valley. Others include Larry Ellison, Oracle’s co-founder, who bought all but a tiny amount of the island of Lanai and turned it into a resort — investing millions, but frustrating some islanders by driving up rents — and Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, who was called a “neocolonialist” after he sued some locals over beachfront land he bought. (He dropped the suits.)

The goal of Omidyar’s farm — which incidentally is on land owned by the family of Steve Case, another tech billionaire — is to decrease the island-state’s heavy reliance on imported milk, while using sustainable agriculture practices. (The dairy will nonetheless still have to import feed for its animals.)

Some residents, though, object. They and the owners of the major resorts that line this island’s famous beaches, just a little more than 1 mile down the coastline from the dairy site, have worked to block the project.

“We are concerned with odors and flies from the dairy,” said Lisa Munger, a lawyer who represents the Grand Hyatt Kauai Resort & Spa, which successfully sued to force the dairy to do an environmental assessement. “Each dairy cow will produce 90.8 pounds of manure per day — whether there are 699 cows or 2,000 cows, that is a lot of manure.”

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Munger said biting flies can reach the Grand Hyatt, along with “offensive dairy odors.”

Opponents of the Hawaii Dairy drive around with bumper stickers — “No Moo Poo in Maha’ulepu,” as the area of the island where the dairy would go is known — summarizing their main cause of concern: that animal waste could contaminate drinking water or the oceanfront and cause unpleasant smells. “We’re all for local agriculture, but why put a dairy there?” said Bridget Hammerquist, a lawyer and the president of Friends of Maha’ulepu, a nonprofit set up to fight the dairy. “It’s a serious threat to Kauai’s biggest source of revenue, tourism; to the environment; and to our quality of life.”

So far, courts have sided with opponents of the dairy. In a case brought by the Friends group, contending that the dairy would violate the federal Clean Water Act, a judge ruled that it had violated the law by failing to get the permits it needed for the construction it had already done on the site.

Another lawsuit, brought by the owners of the Grand Hyatt, contended the dairy would have a negative effect on businesses and resorts along the coast. This year, Judge Randal G.B. Valenciano revoked all permits that had been granted to Hawaii Dairy Farms and ordered it to complete an environmental assessment before going further.

Amy Hennessey, director of communications at the Ulupono Initiative, Omidyar’s investment office in Hawaii, said those decisions were a setback for Hawaiian agriculture and food security, which has been a concern of Gov. David Y. Ige. Hawaii imports roughly 90 percent of its food supply, and Ige has pledged to double the state’s food production by 2020.

The dairy’s representatives contend that the soil at the site can absorb and filter the manure runoff from 699 milk cows. The chosen number of cows is significant: If Hawaii Dairy’s plans included one more cow — bumping the total to 700 — it would meet the Environmental Protection Agency’s definition of a large concentrated animal feeding operation, or CAFO.

That designation initiates the need for a permit under the EPA’s Pollutant Discharge Elimination System. Because the dairy drew the line at 699 cows, avoiding the need for the discharge permit, it originally was able to describe itself as “zero discharge.”

“It’s going to be zero discharge from the EPA’s perspective,” Hennessey said. “There will be very little discharge, but I think it was a little confusing for some people in the community, so we’ve stopped saying that,” she said.

The dairy plans to eventually have 2,000 cows on the property.

The Omidyars have lived in Honolulu more or less full time since the mid-2000s, and it is not the eBay billionaire’s first run-in with the Kauai community. He previously planned to open a resort on the island’s north shore on a property that was home to a Club Med. But he had to give up after about a tenth of the island’s population signed a petition against the project, claiming its impact on the environment would be detrimental.

The very isolation he and other billionaires prize is also the cause of one of Omidyar’s biggest concerns about the state — its need to import most of the food it consumes. That, in turn, explains his interest in setting up a dairy. In a rare interview with The Honolulu Advertiser in 2009, Omidyar noted that Hawaii had enough food to go without imports for just 11 days.

Hawaii has at least three commercial dairies already — and making money is “an uphill battle,” said Steve Whitesides, the owner of one of them, Big Island Dairy. Permits are hard to get, expenses are high, and he has had to import more feed than he expected, he said. Whitesides, an Idaho-based dairy farmer, bought Big Island Dairy in 2012, when it was flirting with bankruptcy.

Recently, the state department of health fined Big Island Dairy $25,000 for illegally allowing animal waste to flow into local water supplies. The tiny town of O’okala sits below the 2,500 acre Big Island Dairy, and its residents had long complained to the state about bad smells and wastewater in the gulches and waterways that run through their yards and streets on the way to the ocean.

© 2017 The New York Times Company