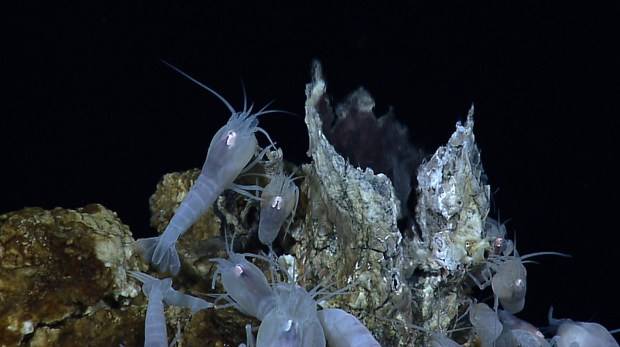

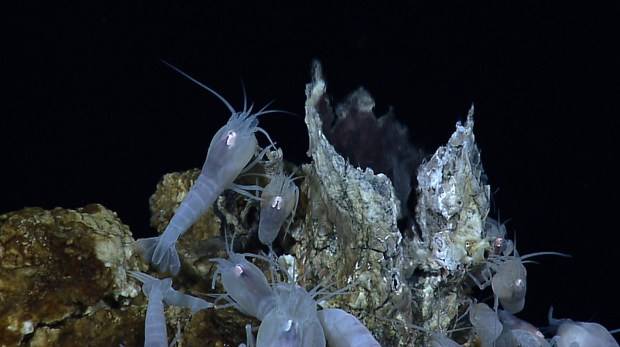

COURTESY NOAA OFFICE OF OCEAN EXPLORATION AND RESEARCH

A team of scientists is warning of the unavoidable damage deep-sea mining would inflict on biodiversity. Cayman vent shrimp gather at a hydrothermal vent.

Select an option below to continue reading this premium story.

Already a Honolulu Star-Advertiser subscriber? Log in now to continue reading.

A University of Hawaii oceanography professor

is among an international team of scientists, economists and legal scholars warning that loss of biodiversity needs to be counted among the unavoidable

and possibly irrevocable costs of deep-sea mining.

The team argued its points in a letter published in the June 26 online version of the journal Nature Geoscience.

In the letter, Craig Smith from UH’s School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology and his colleagues assert that the

International Seabed Authority, which is charged with regulating undersea mining in areas outside of national jurisdictions under the United Nations Law of the Sea, needs to recognize the threat to biodiversity and communicate that to UN member states and the public. The team said such information needs to be part of any discussion about whether deep-sea mining should proceed and what can be done to minimize its negative impact on biodiversity.

“The extraction of nonrenewable sources always

involves trade-offs,” said Linwood Pendleton, international chairman in marine ecosystem services at the European Institute for Marine Studies and an adjunct professor at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, in a release June 28. “A serious trade-off for deep-sea mining will be an unavoidable loss of biodiversity, including many species that have yet to be discovered.”

While there are no current mining operations for undersea metals and rare earth elements, the number of applications for such projects has increased. It is expected that by the end of the year, there will be 27 deep-sea mineral exploration projects, including 17 in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone between Hawaii and Central America.

In the release, the team noted the suggestion by mining supporters that restoring coastal ecosystems or creating new artificial offshore reefs could help offset biodiversity losses due to deep-sea mining.

UH’s Smith dismissed the notion, stating: “The argument that you can compensate for the loss of biological diversity in the deep sea with gains in diversity elsewhere is so ambiguous as to be scientifically meaningless.”

The authors cited the example of one proposed mining project that would impact an area larger than the state of Maine some

3 miles beneath the surface of the ocean as an example of how difficult it would be to remediate damage after the fact.