Archaeologist’s career island-hops through Polynesian cultures

COURTESY UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS

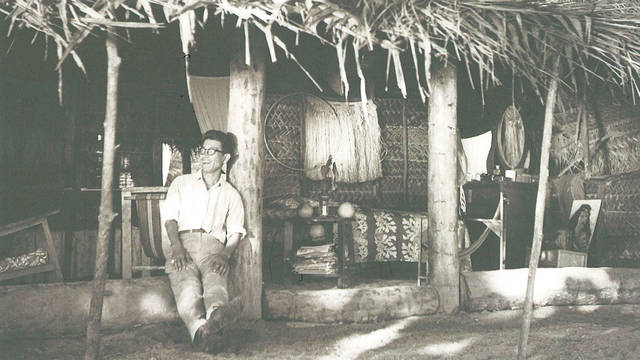

“Curve of the Hook” summarizes the career and philosophy of Yosihiko Sinoto, senior archaeologist at Bishop Museum, for which he has conducted research since 1954.

Composed of recollections, photographs and illustrations, “Curve of the Hook” — equal parts personal and scientific history — summarizes the career and philosophy of Yosihiko Sinoto, senior archaeologist at Bishop Museum, for which he has conducted research since 1954. Told in his own words through a series of transcribed interviews with natural historian Hiroshi Aramata, this remarkable yet unassuming story reflects the man as well as his enlightening work throughout Polynesia.

Originally published in Japan as “Rakuen kokogaku” in 1996, the biography appears here in English for the first time in a translation by Frank Stewart and Madoka Nagado. The text has been updated and revised, with photographs from Sinoto’s own collection, taken over a span of 60 years and depicting people and sites of all ages.

Born in Tokyo on Sept. 3, 1924, Sinoto’s interests took him from his native Japan to the vast reaches of the Pacific Ocean. From Aotearoa (New Zealand) to Rapa Nui (Easter Island), he excavated ancient habitation sites, carried out restoration projects and recovered and preserved artifacts and architecture. He came to know, recognize and respect the diverse peoples of the Pacific and contribute to the elevation and understanding of their history and culture.

His dedication to studying the past began with a boyhood encounter with a prehistoric Jomon pottery shard found in his schoolyard. This led to a successful career researching Japanese archaeology that eventually expanded into the Pacific, where, however, he found very little pottery. Because pottery is an almost universal form of human debris that archaeologists use to establish timelines and geographies of development, its absence in Polynesia led to racist theories that assumed its indigenous people were bereft of history and achievement.

Sinoto shattered this belief by looking at fishhooks instead of pottery shards as a means of measurement. He got the idea while unearthing fishhooks from a sand dune at Ka Lae (South Point) on Hawaii island, where he “observed that the hooks varied considerably in form and material, depending upon the depth at which they were found,” Eric Komori writes in the introduction.

By identifying consistent techniques of fishhook shaping and construction, and carefully tracking their appearance in sites on islands across the Pacific, Sinoto was able to construct patterns of migration between them. Often the stories told by his careful consideration and classification of hooks echoed or were reinforced by Polynesian legends, such as those recounting voyages from the Society and Marquesas islands to the Hawaiian archipelago. Indeed, in Huahine, the Society Islands, Sinosi discovered parts of a 65-foot-long voyaging canoe, supporting a history of Polynesian oceanic migration at a time when others doubted it.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Sinoto, who learned Tahitian and started his research from a place of respect, represents the best that science has to offer as a discipline and worldview. “Curve of the Hook” is the story of a life everyone in Hawaii should know about and be inspired to emulate as we witness ongoing threats to the indigenous cultures of Polynesia.

Frank Stewart, co-translator of “Curve of the Hook,” will discuss the book with Eric Komori, Alexander Mawyer and Hardy Spoehr on a panel at the Hawai‘i Book & Music Festival’s Alana Hawaiian Culture pavilion at noon May 6. For full schedule, go to hawaiibookandmusicfestival.com Opens in a new tab.