Funds sought to expand court sessions for homeless

“Right now you cannot force people to go to homeless counseling. With this program the court can do that. This is something that’s worthwhile. We can also get rid of the backlog so the courts can handle the most serious cases.”

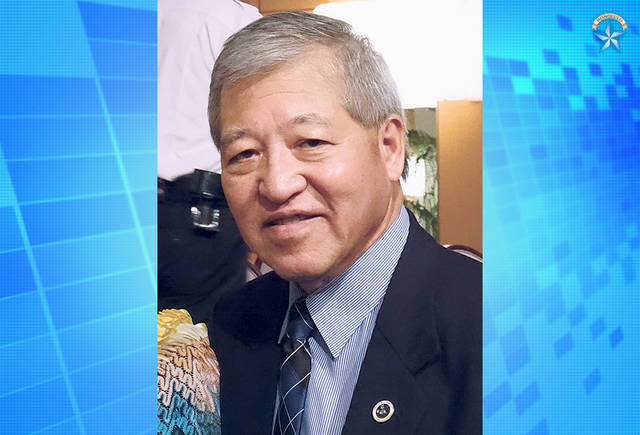

Keith Kaneshiro

Honolulu city prosecutor

The city’s prosecutor and public defender agree that a pilot program to adjudicate low-level, nonviolent offenses for homeless defendants is working.

But the first two monthly sessions of a new “Community Outreach Court” underscore the need to hold court sessions not just in town, but also in Oahu communities where homeless people congregate, commit minor crimes and can serve their sentences by cleaning up where they live, Prosecutor Keith Kaneshiro and Public Defender Jack Tonaki told the Honolulu Star-Advertiser in separate interviews.

“It’s proving to be a success,” Kaneshiro said. “The problem is bringing them (homeless defendants) downtown to court. We need to take the courts to them.”

For example, a District Court judge in the pilot held up court for 30 minutes in January until a disabled, homeless defendant could catch a bus from Sandy Beach to downtown.

While a third consecutive District Court session is planned this month on Alakea Street downtown, Kaneshiro and Tonaki hope legislators approve $612,000 to expand the program to fulfill its original intent of rotating court sessions around the island where homeless people have collectively accrued thousands of outstanding, nonviolent cases such as public drinking, loitering or staying in a park after closing hours.

This afternoon the House Judiciary Committee is scheduled to hear a bill, SB 718, that would fund the program.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

Between fiscal year 2014 and fiscal year 2016, there were 42,662 minor violations committed on Oahu — including 21,763 park violations alone.

“We have a tremendous caseload,” Kaneshiro said. “I think we can clear a lot of these. But there has to be consequences for their actions.”

Kaneshiro said he believes that four to eight hours spent cleaning up public spaces “is fine” for minor violations committed by homeless people. But he is hopeful that getting homeless defendants before a judge also could turn their lives around by ordering them to connect with homeless services.

“Right now you cannot force people to go to homeless counseling,” Kaneshiro said. “With this program the court can do that. This is something that’s worthwhile. We can also get rid of the backlog so the courts can handle the most serious cases.”

With no state funding yet for their idea to take District Court directly to the homeless, Kaneshiro and Tonaki decided to work together on four cases in January and three more in February on the fourth Thursday of the month.

“We originally envisioned it as a mobile court,” Tonaki said. “We decided to go ahead anyway and put something together because we’ve dealt with these cases for years and years. … You’re mostly looking at petty misdemeanors (punishable by) up to 30 days in jail. A lot of people had traffic violations. A lot of them sleep in their car, but a lot don’t have a driver’s license and their cars are unregistered. They have no no-fault insurance, no license. We try to avoid fines because, obviously, why have them pay fines that will never be paid?”

At the start of the first session in January, District Judge Clarence Pacarro could have issued a bench warrant to the tardy, disabled homeless defendant for failing to show up on time, but that would have only exacerbated a problem that Kaneshiro and Tonaki are trying to reduce.

“When people don’t show up, we’re not going to ask for bench warrants” for minor offenses against homeless defendants, Kaneshiro said. “We want to eliminate that process.”

Instead, Pacarro presided over four initial cases that involved 53 violations and 19 outstanding bench warrants in all. He sentenced three defendants to four to eight hours of community service cleaning up around the Judiciary downtown.

The disabled defendant is still working to serve out his community service, Tonaki said. “He uses a walker and has pretty bad infections,” he said.

The following month, Pacarro cleared the court docket of another 56 cases and six bench warrants against three additional homeless defendants and sentenced them to similar community service downtown.

“That’s over 100 cases involving just seven defendants,” Kaneshiro said. “I think that’s a success.”

This month, court space will be included for a social worker from the CHOW Project to immediately try to connect homeless defendants with permanent housing and other services once their court cases are cleared.

A CHOW outreach worker tracked down one of February’s three homeless defendants and is still trying to find the other two, said Heather Lusk, executive director of CHOW, which stands for Community Health Outreach Work to Prevent HIV/AIDS.

“We can help those who are homeless to get connected with benefits,” she said.

Scott Morishige, the state’s homeless coordinator, said the backlog of minor cases often prevents homeless people from getting housing and jobs because they can’t get driver’s licenses that are required.

“It makes it difficult to get into housing and to pursue employment, especially for the chronically homeless population that has been homeless a long time who get caught in parks after hours, have open containers or are living in cars in unlicensed vehicles.” Morishige said. “At the same time, it costs time for the prosecutor. So it’s relieving a huge burden on the courts.”