All in the Family

Sue Kobe, right, and her grandson Kael Yamane go through their exercise routine with Kobe's 98-year-old mother, Harriet Matsuyama. Kobe spends most of her time taking care of her mother. More and more people will find themselves in Kobe's situation as Hawaii's baby boomers move into the ranks of the elderly.

Sue Kobe gives her 98-year-old mother, Harriet Matsuyama, a snack of grapes while Kael Yamane massages his great-grandmother's shoulders. Kobe spends most of her time taking care of her mother but keeps her spirits up by joining a support group for caregivers, sponsored by Project Dana, whose volunteers offer help and compassion to homebound seniors.

Pauline Sumida uses a message board to relay messages to her siblings

June Saito helps her mother, Betsy Suzuki, use a device to obtain a sample for a blood sugar test, part of monitoring the older woman's diabetes. Saito lives in California but returns to Honolulu to take a turn in caring for her mother.

Pauline Sumida uses a message board to relay messages to her siblings, all of whom take care of their mother, Betsy Suzuki. Sumida and one sister handle the weekdays, while another sister and brother take the weekends.

Even at 98, suffering from dementia and no longer able to bathe or dress herself, Harriet Matsuyama has the carefully drawn eyebrows of a lady who wants to look her best.

Her only daughter, Suzanne Kobe, knows appearances matter to her mother. That was always a point of contention between them.

"We never got along," Kobe declared with disarming frankness. "She likes everything neat and nice. She likes you all dressed up, prim and proper."

Despite their differences, for five years now, Kobe’s life has revolved around caring for her frail, 92-pound mother. Once a self-reliant person who pulled apart and fixed lamps and anything else that broke, Matsuyama is now completely dependent. Kobe cooks and serves her meals, keeps her clean and her house tidy, and stays over every night to make sure she is OK.

"It’s become a 24/7 job," said Kobe, who also helps look after her 9-year-old grandson. "My mom said she’s going to live to be 100 — I don’t know if that’s a threat," she added with a laugh.

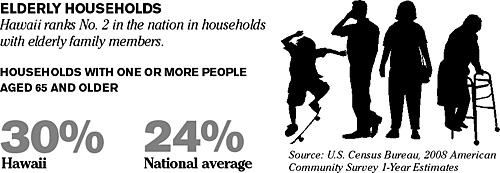

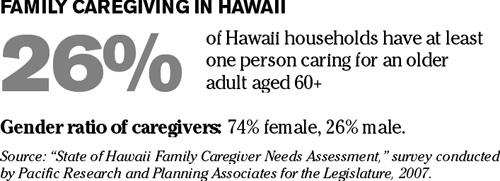

More and more people will find themselves in Kobe’s situation as the population bulge of Hawaii’s baby boom generation moves into the ranks of the elderly. Already, a quarter of Hawaii households have at least one person caring for an older adult, according to a survey conducted for the state Legislature. As people live longer, extended families will stretch further, with more generations needing care.

Don't miss out on what's happening!

Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

In the past, most senior citizens tended to retire, live a few years, then die before reaching the point of needing long-term care. Those who lived longer could usually count on lots of offspring to look after them. That is no longer the case. Baby boomers have fewer kids and rockier marriages than their parents did and are more likely to wind up alone in their twilight years. Also, Hawaii’s children often make their lives an ocean away from their parents.

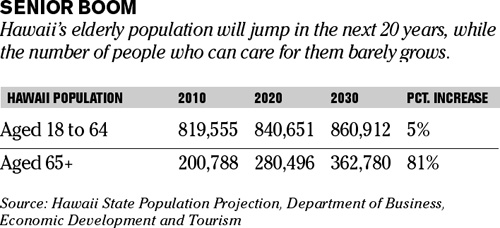

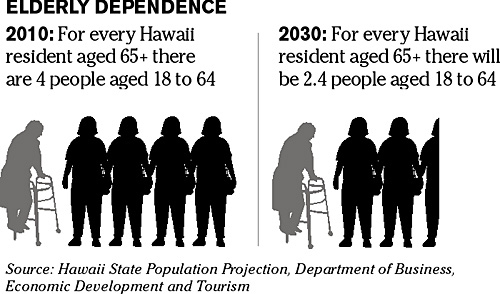

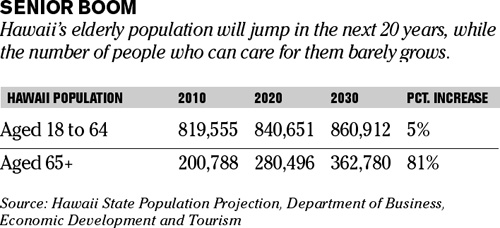

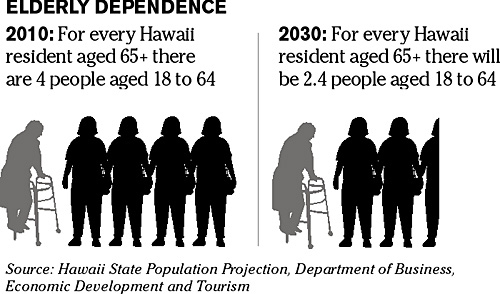

The number of residents 65 and older in Hawaii is projected to shoot up by 81 percent between now and 2030 while the rest of the population grows by just 5 percent, according to state projections. Today, for each person 65 and older in the islands, there are four potential caregivers age 18 to 64. In 20 years the ratio will be closer to two younger adults for every older one.

"This is what’s on the horizon," said Barbara Kim Stanton, AARP Hawaii state director. "This huge boomer group is going to be competing for very meager services. Something has to change. Otherwise, we are heading straight into disaster."

Yesterday » Graying of Hawaii Opens in a new tab Today » Over extended families: Opens in a new tab Hawaii’s high costs and healthful living mean that more senior citizens will be cared for at home. Tomorrow » Booming costs: Opens in a new tab Hawaii is unprepared for the costly combination of more retirees and fewer workers to support them. Thursday » Unhealthy debt: The state has put aside nothing for the expected $10.8 billion in health care costs for government retirees. |

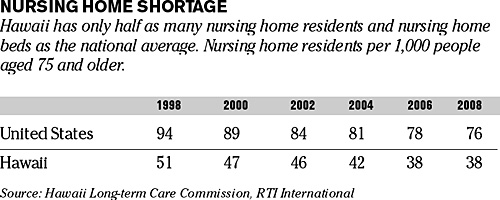

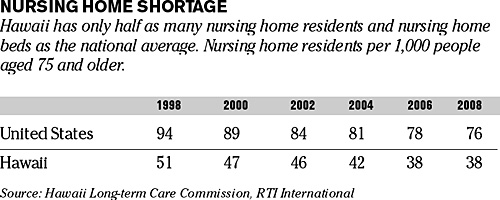

In some ways the situation seems more daunting for Hawaii than other states as it looks ahead to a graying population. Hawaii has only half as many nursing-home beds per capita as the national average. Its facilities are full, and most people cannot afford them anyway. The median occupancy rate in local nursing homes in September was 95 percent, the highest in the country, according to the American Health Care Association. And those Hawaii nursing home slots are pricey: $131,400 per year for a private room, compared with $79,900 nationally, according to the Hawaii Long Term Care Commission.

"Our senior population is growing at a really, really fast clip, about two to three times more than the national average," said Cullen Hayashida, director of the Kupuna Education Center at Kapiolani Community College and graduate affiliate faculty member at the University of Hawaii. "While that’s happening, the nursing home bed supply has remained flat."

Developers come to the islands eager to build nursing homes but soon back away, dismayed by the high cost of land, construction and staffing, and low government reimbursement rates for care, he said. "It does not pencil out," Hayashida said. "They can’t recoup their initial investment."

Instead, Hawaii relies primarily on family caregivers and friends, along with an array of "mom-and-pop" residential care homes of varying quality. At the same time, aging singles and couples in some of Honolulu’s older condominiums are slowly transforming their buildings into de facto retirement communities, but without the necessary services.

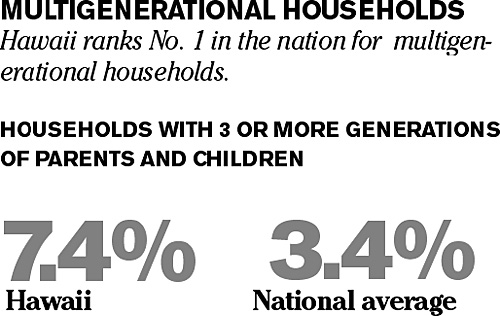

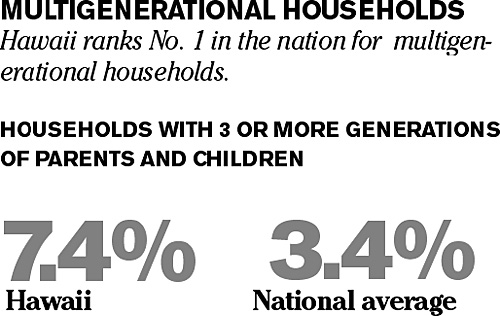

Extended family living comes naturally in Hawaii, both for cultural and practical reasons, as Polynesian and Asian traditions dovetail with the high cost of housing. Hawaii is ranked No. 1 among the states for multigenerational living. Twice as many households here as the national average have three or more generations of parents and their children under one roof, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

"Our system heavily, heavily over-relies on the good will of family and friends," Stanton said. "Unpaid family caregivers provide the vast majority of long-term care services for people with disabilities. The fact that we have such high longevity is wonderful, but we are so ill prepared with a state strategy on aging that seniors, the elderly and frail, are in for rough times."

While family caregiving can bring people together, it also takes a toll. Some people quit their jobs, giving up their chances at earning retirement benefits, or they burn through their nest eggs while caring for their parents. More than half say caregiving has affected their work, and third say it has cut into their personal time and sleep, according to the Executive Office on Aging.

"Unless you have done caregiving, you really don’t know how difficult it is," said Kobe, who is 73. "I live across the way, but I stay with her here because I can’t leave her at night. I’m here 99 percent of the time. You get so you don’t have a life."

Fortunately, Kobe has managed to keep her spirits up by joining a support group for caregivers sponsored by Project Dana, whose volunteers offer help and compassion to homebound seniors. Kobe joins fellow caregivers three times a month for educational sessions, potlucks and excursions.

"I just love it," Kobe said. "They nourish you. When you’re with other caregivers, you can speak freely about everything. They all understand."

Even when there are lots of offspring to share the load, caring for aging parents can be tough. With five children, the Suzuki family of Kaimuki seemed to have a built-in insurance policy for their old age. When Edward Suzuki took a fall in June 2005 and his wife, Betsy, started showing cognitive decline, daughter Pauline Sumida stepped right up to help. She lived nearby and had just retired.

After six months of taking care of them every day by herself, Sumida burned out. The soft-spoken woman realized she had to get help from her siblings. They have been pitching in ever since, although Sumida is still the main caregiver. Their father died last year, and the kids now rotate caring for their 88-year-old mother, 24 hours a day. Sumida and a sister handle the weekdays, and another sister and brother take the weekends.

"I do most of her finances, her planning, take her to the doctor," Sumida said. "I literally run her whole household as well as my own. Her books are up to date, mine are falling behind. My savings have gone down consistently."

"Sometimes I feel torn," she added. "It’s hard for my husband. My immediate family needed to adjust. So sometimes it kind of makes you feel guilty."

The eldest sister, June Saito, flies in from her home at Seal Beach, Calif., for several weeks at a time to offer relief.

"I come twice a year, so I try to stay a long time," Saito said. "Early this year I was here for two months, and it nearly killed me. I’m there 24/7. At home I’m in total control of my life. When I come here I have no control."

"She has always expected that the children would take care of her," Saito added. "If we were to put her in a nursing home, she would feel so abandoned."

A national survey of seniors underscores that concern. Seniors 65 years and older said they feared moving to a nursing home more than they feared death, according to the 2007 poll "Aging in Place in America," commissioned by Clarity/The EAR Foundation. Asked to name their greatest fear, 26 percent said "loss of independence," followed by 13 percent who said "moving to a nursing home." Death was named by just 3 percent.

The vast majority of seniors — 90 percent — want to stay in their homes as they age, according to AARP. National and state governments are pushing to have more seniors cared for at home or in small residential care homes, in hopes of keeping down costs and providing a homier, less institutional setting. But oversight has not kept up with the expansion of care homes, here and nationally.

"States across the country are really struggling with how to regulate these facilities," said Joshua Wiener, program director for aging, disability and long-term care with RTI International in Washington, D.C., which is working with Hawaii’s Long Term Care Commission.

Finding a good foster home can be a shot in the dark when a frail senior is discharged from the hospital or families can no longer care for an elder at home. While Medicare.gov has an online database to compare nursing homes for quality of care, no similar tool is available for small care homes that cater to a few elders at a time. A bill to require online posting of inspection reports on licensed community care homes passed the state Senate unanimously last year but died in the House.

"Family members seeking placement for a parent or grandparent are often at a loss," Anthony Lenzer, emeritus professor and former director of the Center on Aging at the University of Hawaii, testified at a legislative briefing in September. "What families need but often don’t have is reliable, objective information about the facility where grandpa would be going."

Paying for long-term care is another hurdle. Only 10 to 20 percent of seniors can afford high-quality long-term care insurance, Wiener said. And Medicaid, which covers nursing home care for the poor, has tightened eligibility requirements to prevent middle-class seniors from shedding assets to qualify for it.

The new national health care law includes a voluntary insurance program for long-term care, with the cost to be covered by premiums. Only working people may enroll, and they must pay premiums for five years before becoming eligible for benefits. A state plan to finance long-term care benefits with an income tax was vetoed by Gov. Linda Lingle in 2003.

June Saito is already prepared for when her role shifts from caregiver to care recipient. Instead of presents for special occasions every year, her only daughter decided to give Saito a long-term care insurance policy and pay the annual premiums. In some ways it is a gift to both generations.

"She knows she wouldn’t be able to keep her job and take care of me at the same time," Saito said. "That’s why she gave me that as a gift, for my birthday and Christmas."

The issue of long-term care is not high on the local agenda, but it should be, advocates say.

"One of the problems is long-term care is not a cheerful subject," said Eldon Wegner, president of the board of the Hawaii Pacific Gerontological Society. "People don’t want to think about it. They don’t want to think they’re going to get there."

"Everyone has to realize we all have to pay for this," Wegner said. "Everybody has to play their part. They say it takes a village to raise a child, but it also takes a village to care for our older population."

HELP IS OUT THEREHere are some resources to help seniors, their caregivers and people preparing for an active old age. State of Hawaii Aging and Disability Resource Center County Agencies on Aging: Elderly Affairs Division Honolulu Hawaii County Office of Aging Kauai Agency on Elderly Affairs Maui County Office on Aging Alzheimer’s Association Aloha Chapter Catholic Charities Hawaii Child & Family Service Kupuna Education Center "Kupuna Connections" Project Dana State Executive Office on Aging |