The art of architecture in Hawaii

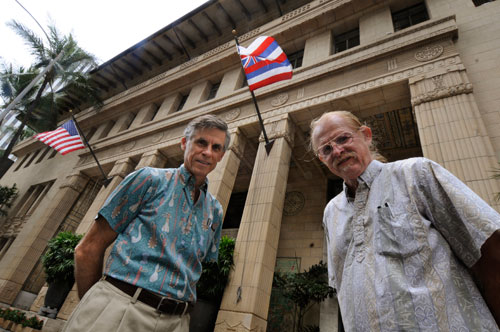

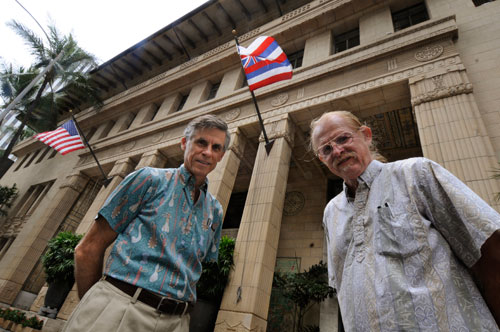

Glen Mason, left, of Mason Architects and architectural historian, Don Hibbard, authors of "Hart Wood: Architectural Regionalism in Hawaii," stand in front of the Hart-designed Alexander & Baldwin Building.

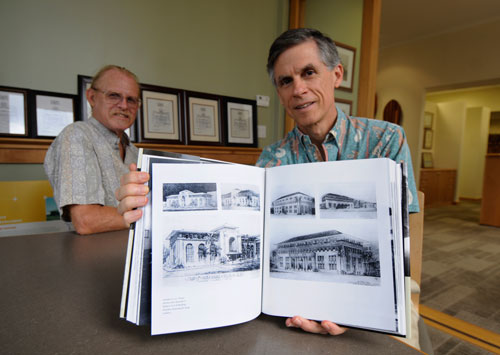

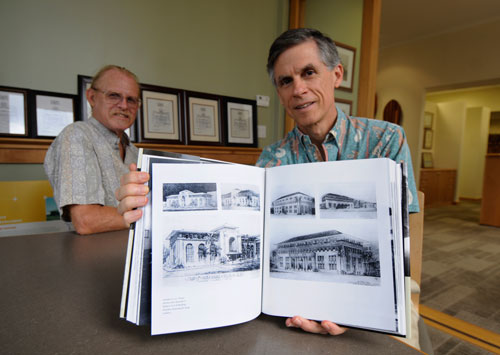

Glen Mason, center, with Don Hibbard, with their new book open while inside the Alexander & Baldwin Building. The original drawings in "Hart Wood: Architectural Regionalism in Hawaii" show the progression from a more simple building to the more grand Alexander & Baldwin Building.

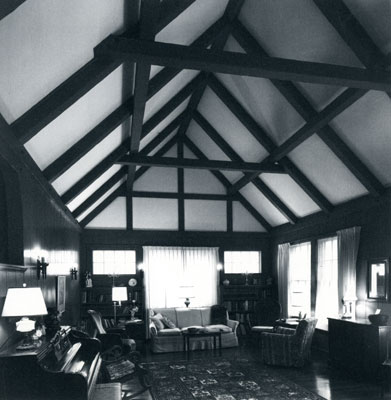

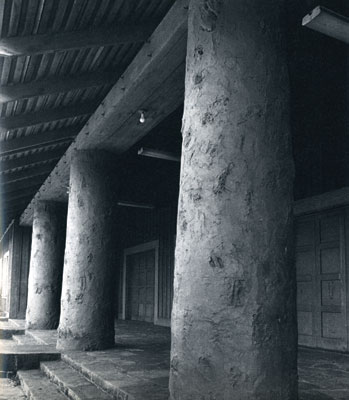

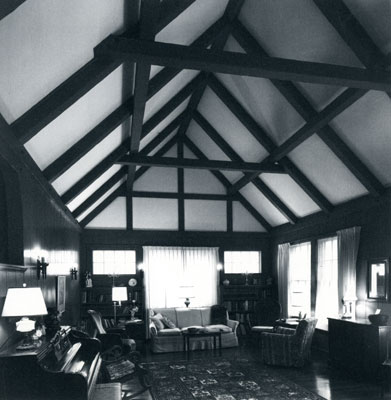

The Austin residence interior in Honolulu is an example of the quality of Hart Wood's work.

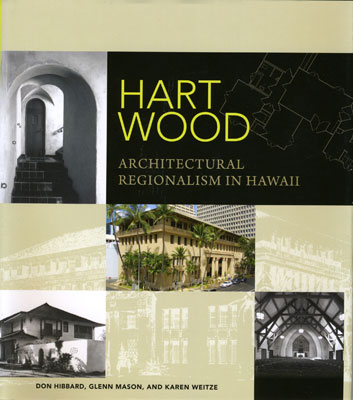

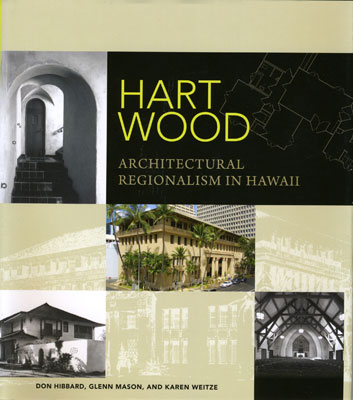

"Hart Wood: Architectural Regionalism In Hawaii" By Don J. Hibbard, Glenn E. Mason and Karen J. Weitze (University of Hawaii Press, $24.95)

Several people stand outside of the Makiki pumping station, an example of Hart Wood's regional architecture in Hawaii that influenced many buildings.

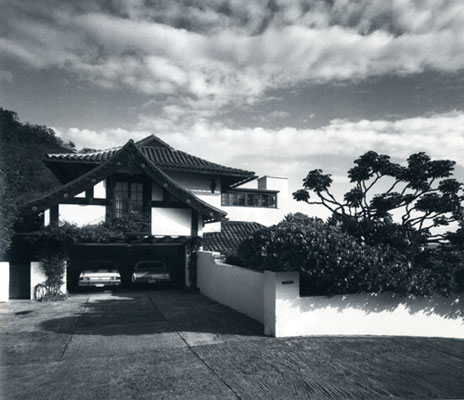

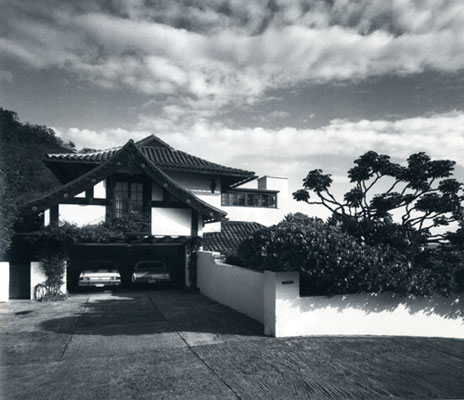

The Pew residence in Honolulu.

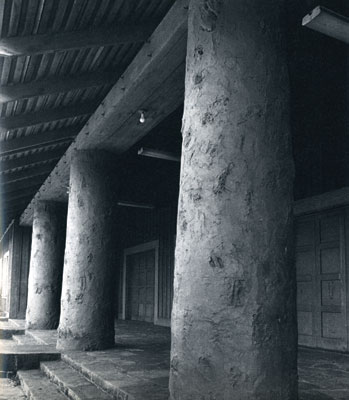

The Waimea Community Center on Kauai.

Mies van der Rohe may have shrugged off architecture as what begins when one puts two bricks together, but seriously, it’s the second-oldest profession, born when the oldest profession needed its own room.

Although we are surrounded by the works of architects past and present, few can tell a soffit from an apse, much less the simple stuff. So works about architects are always welcome, particularly when they tell us something about our own built landscape. The new University of Hawaii Press book "Hart Wood: Architectural Regionalism in Hawaii," pictured below, is a valuable addition to the rather thin selection of volumes about Hawaii architecture.

So why are most of the pictures in the book taken in the early ’80s?

Authors Glenn Mason and Don Hibbard glanced at each other, just a little sheepishly. "Well," said Mason, "that’s when we, ah, started working on this."

Architect Mason is now likely the state’s resident expert in historic renovation, and Hibbard is the retired head of the state Historic Preservation Division. A third author, Karen Weitze, is a researcher living on the mainland. But in the early ’80s, Mason was working on oral histories of local architects, and Hibbard was preparing preservation documentation for the government. Both of them kept running across Wood’s name.

"HART WOOD: ARCHITECTURAL REGIONALISM IN HAWAII"By Don J. Hibbard, Glenn E. Mason and Karen J. Weitze (University of Hawaii Press, $24.95) Don't miss out on what's happening!Stay in touch with breaking news, as it happens, conveniently in your email inbox. It's FREE!

By clicking to sign up, you agree to Star-Advertiser's and Google's Terms of Service Opens in a new tab and Privacy Policy Opens in a new tab. This form is protected by reCAPTCHA.

|

Wood arrived in Hawaii in 1919 from Oakland, Calif., in partnership with another architect who became well known in the isles, C.W. Dickey. They became fascinated with developing a "regional" architecture for Hawaii, until then characterized by inappropriate European and American Beaux Arts imports.

"We were interested in finding out how these architects did their jobs," said Mason. "Was this interest in regionalism something that evolved?"

Hibbard suggests interest in the types of architecture that came in with U.S. annexation may have been wearing off by the 1920s. "Dickey and Wood began designing with Hawaiian living spaces in mind, opening up interiors, creating lanais, adding hipped roofs," he said.

This was a period thought by many to be a golden period of Hawaiian municipal architecture. Buildings we take for granted today as expressions of "local" design — the Alexander & Baldwin Building, Honolulu Hale, the Federal Building/Post Office, dozens for Board of Water Supply pumping stations — were created by Dickey and Wood after extensive design iterations. Ideas were absorbed from as far apart as Italy and China. Wood, in particular, had a genius for decorative detail that dovetails smoothly with the overall aesthetic. Look around the Honolulu Hale courtyard at the Italianate detail. That’s Wood. The Chinese-y perforations in the Honolulu Hale tower and walls? Wood again.

"No one comes close to Wood’s eye for detail and decoration," said Hibbard.

"A very eclectic architect, ranging from Tudor exposed-beam styles to Chinese stucco to pretty modern metal-and-glass structures," said Mason. "And he was a terrific artist, too. I wish I could draw like him."

"Wood also employed James Tomita, a top draftsman," Hibbard noted. Tomita was responsible for much of the technical rendering in the later years of Wood’s career and was one of Hibbard’s sources on Wood’s work. Wood himself was notoriously close-mouthed.

Mason thinks this "golden age" is overblown. "It’s a popular stereotype. Basically, it just means Mediterranean styles. There were very interesting styles and designs in the 1950s, too. Chinatown, on the other hand, stopped about 1925."

But Wood, Dickey and others "were certainly having conversations about regionalism," said Mason. "They came from the Bay Area, where architects were firmly creating a regional style in the early century. But were they getting together and talking about it, planning it? No. It evolved and they were aware."

"There are letters they sent back and forth in which they’d wonder if something looked ‘Hawaiian’ or not," said Hibbard. "Wood did a lot of work with (longtime kamaaina family) the Cookes, and Mrs. (Anna C.) Cooke’s Chinese art collection influenced him."

"Her sensibilities steered him," said Mason.

"A lot of his architectural world centered around her," Hibbard agreed.

"And so, Hart Wood ends up thinking of Hawaii as a crossroads, with influences from everywhere," said Mason.

"At the time, there was a real pan-Pacific movement in much of the arts," said Hibbard. "Even the term ‘crossroads of the Pacific’ comes from that era."

Hart Wood died in 1957; Dickey died in 1942. Between them, and others, a kind of Hawaii "regional" architecture was born.

So now, in the modern era, we’re surrounded by Hart Wood designs, and the book is just now being released. Again, what took so long?

"We started working fairly seriously in the mid-’80s, with basic recordation of things," said Mason. "And then, we just … ran out of steam."

"Families. Work. Life," mused Hibbard.

"Yes. And then, about four years ago, we just looked at each other and said, ‘This is nonsense. Let’s get it over with.’"

With some financial help from Alexander & Baldwin and the Atherton Foundation, research and writing were completed, and University of Hawaii Press picked up the project.

"A matter of relief," said Mason.